Cependant des démons malsains dans l'atmosphère

S'éveillent lourdement, comme des gens d'affaire,

Et cognent en volant les volets et l'auvent.

À travers les lueurs que tourmente le vent

La Prostitution s'allume dans les rues;

Meanwhile in the atmosphere malefic demons

Awaken sluggishly, like businessmen,

And take flight, bumping against porch roofs and shutters.

Among the gas flames worried by the wind

Prostitution catches alight in the streets…

Baudelaire, Le Crépuscule du soir (tr. Aggeler).

In the dim light, the ladies of the night stride forward… seeping from the mad head of Galliano… they skulk under Pont Alexandre III. Pale with grim sickness… damp… cold… they sin to keep on living.

The fin-de-siècle, muted, muddy, soggy and sepia, has come to Paris. Its glamour taken underground. Finally, the unseen and the unknown are seen and known.

Theatre, as truth, a spectacular pestilence, spreads from soul to soul. The audience, infected, disturbed, are inflamed by holy fire.

Antonin Artaud, le suicidé de Dieu

“Who am I?

Where do I come from?

I am Antonin Artaud

and I say this

as I know how to say this

immediately

you will see my present body

burst into fragments

and remake itself

under ten thousand notorious aspects

a new body

where you will

never forget me.”1

Those whom the gods wish to destroy, they first make mad. And yet, those whom the gods wish would create, they also make mad. Antonin Artaud and John Galliano did create. Their genius—spinning, maddening, deteriorating—spawned endless wonders, representations of the divine. Their fabrications, though stitched together with such mania, convey the glistening coherence of the master craftsman. At no point did they cease creating: their divinely inspired minds relentlessly drove them on.

In understanding these minds-divine, I have so far tracked each man’s personal and creative development, making clear their personalities, eccentricities and aesthetic ideologies, while bringing crucial context. Galliano and Artaud are The End by The Doors, screeching through the jungles of Vietnam. Galliano and Artaud are the ‘Presto’ movement of Scriabin’s Sonata No. 2, whose storms could capsize Ravel’s Une barque sur l'océan. Galliano and Artaud are Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du printemps unleashing ‘The Savage God’ upon the world. Yet much difficulty remains in characterising these men and their works. Genius necessarily brings a certain unknowability. Similarly, an asymmetry of theory and practice must inform any reading of these figures. Throughout his career, Galliano was able to enact his vision of haute couture, yet rarely put it into words. Artaud, by contrast, composed much theory, yet was scarcely able to put it into practice. This suits our purposes; Artaud’s theory will serve to explain Galliano’s practice. Within this context, then, I shall aim, in this second essay of the series, to outline my Artaudian thesis of Maison Margiela’s 2024 Artisanal Collection. In this collection, Madness married Genius, and begat Beauty.

As mentioned, though Artaud produced abundant written works, with accompanying theory, he was unable ever to realise his dramatic project—at least, not in his fairly brief and tortured lifetime. Even when he did stage plays in line with this project—those at Théâtre Alfred Jarry and Les Cenci—he complained that the audience, intentionally seeking out avant-garde performances, were too tolerant of his strange methods. Since these productions were “too avant-garde for the general public”, they only attracted the “I was there or flippant sort.”2

Over time, however, Artaud’s works “continue to richochet strongly through contemporary culture.”3 Susan Sontag calls his impact “so profound that the course of all recent theater in Western Europe and the Americas can be said to divide into two periods—before Artaud and after Artaud.”4 He has influenced the philosophy of Derrida, Deleuze, Guattari and Kristeva, the art and film-making of Baselitz, Schnabel and Fassbinder, and theatre such as Peter Weiss’ Marat/Sade and Adamov’s Theatre of the Absurd. Artaud’s influence has even spread as far as Japan—Butoh, a sort of dance theatre has “approached Artaud’s work with its painfully contorted imagery of the dancing anatomy, steeped in desire… violent and erotic”.5

So did others succeed where Artaud himself failed? Marat/Sade or Butoh, for instance, could be considered partial fulfilments of his ideals.6 Even so, there exists a strong current among dramatists and critics that sees Artaud’s ideas as thought-provoking, but not actually useful for staging theatre. The great Peter Brook, even after pioneering Artaud and his Theatre of Cruelty with the Royal Shakespeare Company, still believed that:

“Artaud has no relation with practical theatre […] The people I know who either worked with Artaud or saw his work found that in fact, it never led to any good results and his productions were extremely disappointing.”7

So was it the medium that was wrong? Does theatre, as we conventionally expect of it, become too self-conscious if the director attempts to fulfil an avant-garde vision that shatters expectations? Were Artaud’s ideas simply too radical for the form? So radical that audiences, made wretched by their prejudices, were unable to take it seriously? And, worse even, those receptive to avant-garde were too tolerant?

What, then, is the relation of art to its audience? For whose benefit is it made? As I have previously argued,8 poetry is for each and every one of us, since it serves a didactic purpose, not just from learning its content, but from understanding the “relation of expression to meaning”,9 and thus the relation of man to society. I have also urged a limitless understanding of poetry, and thus art, as an ‘expression of reality in irreality.’10 As we shall see, Artaud took a similar line; theatre had the power to create a ‘double’, that is, true reality. Yet, Artaud’s theses have, if anything, been over-intellectualised. Saul Bellow (in the voice of Charlie Citrine) in Humboldt’s Gift writes:

“Belief only in intellect, which Ferenczi has now charged with madness. But what does that mean in a larger sense? It means that the only art intellectuals can be interested in is an art which celebrates the primacy of ideas. Artists must interest intellectuals, this new class. This is why the state of culture and the history of culture becomes the subject matter of art. This is why a refined audience of Frenchmen listens respectfully to Artaud screaming. For them the whole purpose of art is to suggest and inspire ideas and discourse. The educated people of modern countries are a thinking rabble at the stage of what Marx called primitive accumulation. Their business is to reduce masterpieces to discourse. Artaud’s scream is an intellectual thing.”

Artaud was not interested in ‘critique’ or ‘discourse’, though he has nevertheless suffered from such treatment. In fact, Artaud’s mental struggles were such that he found himself “in constant pursuit of [his] intellectual being.”11 Ideas would “abandon him… he [would rage] against the chronic erosion of his ideas, the way his thought crumbles beneath him or leaks away.”12 Artaud’s conception of theatre as more true than life was deeply characterised by this aversion to ‘transient’ ideas. Artaud gives us an example (the ‘double’): an actor’s fury, expressed by his physical and mental incandescence, “remains enclosed within a circle”, due to its ‘factual’ pointlessness, whereas a murderer’s fury “exhausts itself… it has assumed a form, while the actor’s fury, which denies itself by being detached, is rooted in the universal.”13 Artaud was on a mission to find the truth, which he wished to impart not just to a select group of intellectuals, but to the culture at large.14 That truth was the Theatre of Cruelty—“it seems to me the best way of producing this concept of danger on stage is by the objective unforeseen, not unforeseen in situations but in things, the sudden inopportune passing from a mental image to a true image.”15

The Theatre of Cruelty

“If our lives lack fire and fervour, that is to say continual magic, this is because we choose to observe our actions, losing ourselves in meditation on their imagined form, instead of being motivated by them.”—Antonin Artaud, The Theatre and Its Double16

“The habit of thinking prevents us at times from experiencing reality, immunises us against it, makes it seem no more than another thought. There is no idea that does not carry in itself its possible refutation, no word that does not imply its opposite.”—Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time.17

“There are more things, Lucilius, likely to frighten us than there are to crush us; we suffer more often in imagination than in reality.”—Seneca, On Groundless Fears.18

Phrased another way, poetry, and theatre, being poetry, evokes a sustained state of attention, that is, paying attention to the life right in front of us, in an elevated state. The base state of man takes life, and all its things, for granted. This is necessary for survival; yet, reduces us to mere beasts. In the irreality, or superreality, of poetry we become divine, sensing the higher principles that guide us, while simultaneously becoming cognisant of our own mortality. Suddenly we hear the sounds of the wind, the shaking of the trees, see the falling leaf and petal, and the realisation strikes us that we’re alive. We don’t know why, but we do know that we ARE alive.19

With such restlessness did Antonin Artaud live his life. Certainly he was possessed by Yeats’ ‘Savage God’; yet the chaos that defined him always manifested itself in pure, effusive purpose. This was another reason why he and the Surrealists went their separate ways. While he was “always extremely conscious, intentional and wilful”, the Surrealists preferred to cultivate their “unconscious reflexes”, in pursuit of the “psychic automatism in its pure state.”20 Artaud, instead, believed in a more purposeful, aggressive set of actions, that would enable access to the poetic state: his Theatre of Cruelty. So, what is the Theatre of Cruelty?

There are two cardinal concepts:

The ‘double’, which, as I have discussed, “is the real”,21 not of ‘real life’, but of the metaphysical realm: “theatre ought also to be considered as the Double not of this immediate, everyday reality which has been slowly truncated to a mere lifeless copy, as empty as it is saccharined, but another, deadlier archetypal reality in which Origins, like dolphins, quickly dive back into the gloom of the deep once they have shown their heads.”22

‘Cruelty’, being “the sense of hungering after life, cosmic strictness, relentless necessity, in the Gnostic sense of a living vortex engulfing darkness, in the sense of the inescapably necessary pain without which life could not continue.”23 For Artaud, in life, “evil is the paramount rule, whatever is good is an effort.”24 ‘Cruelty’, then, is the cultivation of a purposeful, strict, aggressive intention, aimed at an “inexorable goal, whatever the cost.”25 In Artaud’s, and theatre’s case, the ‘double’.

Reformulating his definition of theatre in these terms, Artaud declares that “theatre in the sense of constant creation, a wholly magic act, obeys this necessity. A play without this desire, this blind zest for life, capable of surpassing everything seen in every gesture or every act, in the transcendent aspect of the plot, would be a useless and a failure as theatre. “26

The fallen state of contemporary theatre needed a unique revival, only possible because of its unique position among the art forms as having a “physical aspect” and “[requiring] spatial expression (the only real one in fact).”27 As such, “in our present degenerative state, metaphysics must be made to enter the mind through the body.”28

‘Cruelty’ did not necessarily mean the use of vulgarity, screaming, and other bodily movements in theatre, “at least not exclusively so.”29 Such elements were, however, “essential parts of [Artaud]’s aesthetic and theatrical vision”— “where violent physical images pulverise, mesmerize the audience’s sensibilities, caught in the drama as if in a vortex of higher forces.”30

What, then, does a staged play, based on the Theatre of Cruelty look like? Artaud goes into much detail in his manifestos, only the most significant parts of which I shall include below:

The Show: “Every show will contain physical, objective elements perceptible to all. Shouts, groans, apparitions, surprise, dramatic moments of all kinds, the magic beauty of the costumes modelled on certain ritualistic patterns, brilliant lighting, vocal, incantational beauty, attractive harmonies, rare musical notes, object colours, the physical rhythm of the moves whose build and fall will be wedded to the beat of moves familiar to all, the tangible appearance of new, surprising objects, masks, puppets many feet high, abrupt lighting changes, the physical action of lighting stimulating heat and cold, and so on.”31

“These means… can only achieve their full effect by using discords. Instead of restricting these discords to dominating one sense alone, we mean to make them overlap from one sense to another.”32

Staging: “The old duality between author and producer will disappear, to be replaced by a kind of single Creator using and handling this language, responsible both for the play and the action.”33

Stage Language: “ordinary objects, or even the human body, raised to the dignity of signs”.34

Interpretation: “The show will be coded from start to finish, like a language. Thus no moves will be wasted, all obeying a rhythm, every character being typified to the limit, each gesture, feature and costume to appear as so many shafts of light.”35

Stage — The Auditorium: “We intend to do away with stage and auditorium, replacing them with a kind of single, undivided locale without any partitions of any kind and this will become the very scene of the action. Direct contact will be established between the audience and the show.”36

“By eliminating the stage, shows made up and constructed in this manner will extend over the whole auditorium and will scale the walls from the ground up along slender catwalks, physically enveloping the audience, constantly immersing them in light, imagery, movements and sound. The set will consist of the characters themselves, grown as tall as gigantic puppets, landscapes of moving lights playing on objects or continually shifting masks.”37

“And just as there are to be no empty spatial areas, there must be no let-up, no vacuum in the audience’s mind or sensitivity. That is to say there will be no distinct divisions, no gap between life and theatre.”38

Works: “We will not act written plays, but will attempt to stage productions straight from subjects, facts or known works.”39 “These themes will be universal, cosmic, performed according to the most ancient texts taken from Mexican, Hindu, Judaic and Iranian cosmogonies, among others.”40

Artaud laid out the praecepts of his Theatre of Cruelty, and, since he did not fully accomplish them in his own lifetime, we must take them up, and pursue the truth, in all its cruelty.

Galliano’s Theatre of Cruelty

“[Sensuality] is as important as eating good food, or drinking a good wine, something that perhaps we are taking for granted and we aren’t enjoying as much as we should.”41

“The moment you put on my clothes you should feel as proud as a bird and move accordingly.”42

“We need the parfum. We need the essence. The undiluted creativity, which is artisanal. Only then, I feel, can we exploit that into the ready-to-wear, or the eau-de-toilette, or eau-de-parfum, and so on… Right down though to the accessories. Success needs coherence, of a brand.”43

—John Galliano.

Antonin Artaud set out, with his Theatre of Cruelty, “to restore an impassioned, compulsive concept of life to theatre.”44 John Galliano restored the same to haute couture. His collections, and their shows, have been radical, theatrical and fantastical, pushing the envelope since Les Incroyables, through to Givenchy and Dior, until today, at Maison Margiela. To be sure, not every collection reached the heights of sublimity, but given Galliano was designing thirty-two Dior and John Galliano collections a year at the time of his 2011 scandal, this was inevitable. However, some do stand out, such as The Ludic Game (A/W 1985-6), The Black Show (A/W 1994-95), and Marchesa Casati (Dior S/S 1998), among others.

Our case study, the Maison Margiela 2024 Artisanal Collection represents the mature culmination of Galliano’s life achievements, and aesthetic philosophy, as a couturier and designer. While remaining a fantastist, he has left behind the fantasy of excess in favour of the fantasy of truth. Through this, I have come to realise that, perhaps, it is the fashion show, or, at least, Galliano’s fashion show, that is the true heir of Artaudian thought. The Theatre of Cruelty was acted out on the streets of Paris, at last.

As I have established, then, theatre, in the conventional, expected sense, suffers from a great insufficiency. An avant-garde production attracts only those who are too tolerant of the avant-garde. These same people often have a tendency to overintellectualise and, as Artaud would say, “choose to observe [their] actions, losing [themselves] in meditation on their imagined form, instead of being motivated by them.”45 We require, instead, a format that is not so self-conscious: the fashion show.

Now, that probably sounds absurd—surely the fashion show, and fashion more generally, is thoroughly self-conscious? After all, it is a form of expression based entirely on appearances. True, perhaps, on the surface; yet, fashion’s relationship with expression, and particularly theatrical expression is more complicated than that. We must remember that the ultimate purpose of the fashion show is to sell clothes. Indeed, haute couture, in the modern day, is designed as a showpiece for the fashion house to sell the brand. This was Arnault’s great innovation at LVMH, transitioning to an haute couture model that was more interested in publicity than selling individual pieces to high-status individuals. Galliano’s extravagance was ideal for this.

The haute couture fashion show, then, exists at an optimum point where the purpose of the show is not performance, yet the performance does matter. This is the Artaudian optimum—the focus of the audience is dual, and in that sense, unfocussed, and not overintellectualising. It is theatre in its most immediate sense, pulling the audience directly into the spectacle. The audience is not there specifically for the theatre of the event, and so has few expectations that prejudice them against the avant-garde and the couturier’s experimentation. The couturier’s creative impulses generate a Gesamtkunstwerk that exists, at first presentation, as a passionate and beautiful mode. Only once the show ends is the intellectual side investigated, as commentators and critics begin peeling the layers off the façade: the cuts, the ornaments, and the elements of the clothes themselves. The format finds itself fulfilling Artaud’s vision, better than conventional theatre. Now for the Artisanal Collection:

a. Mise-en-scène

In an Artaudian manoeuvre, Galliano does away with a runway, the fashion show’s stage. The models appear from under the arch of Pont Alexandre III, creep through the fog, and snake their way through a grotty underground bar. The audience is arrayed within the scene. What the Black Show (A/W 1994-5) began, the Artisanal Collection perfected. Replaced was the Hotel Particulaire, the residence of aristocrats; in its stead the domain of the downtrodden—of the whore, the beggar, the thief. The models, close-up, are close enough to be touched, if the audience wishes. All can hear the sounds of the flowing Seine, Paris’ eternal artery. The setting is real, yet irreal—Galliano constructs a true reality, suspended in time.

That suspended reality is Galliano’s sketch of immortal Paris—a cosmic myth as Artaud would have wished—and its characters are time-travellers from the city’s many eras. Brassaï’s photography forms the base—his 1930s portraits of Paris’ nocturnal underbelly echo Henry Miller’s.46 Next comes the Fauvism of Kees van Dongen, with his experiments in colour and proportion. Though Galliano explicitly invokes Brassaï and van Dongen as inspirations, his imagined Paris is largely influenced by a prior period—the fin-de-siècle.47 His Paris is the Paris of Baudelaire, Rimbaud and Verlaine: a city mired in decadence and tainted by obscenity. Capping off these visions of Paris come the dolls of the ancien régime, setting old against new, and aristocracy against underclass, all frozen in time.

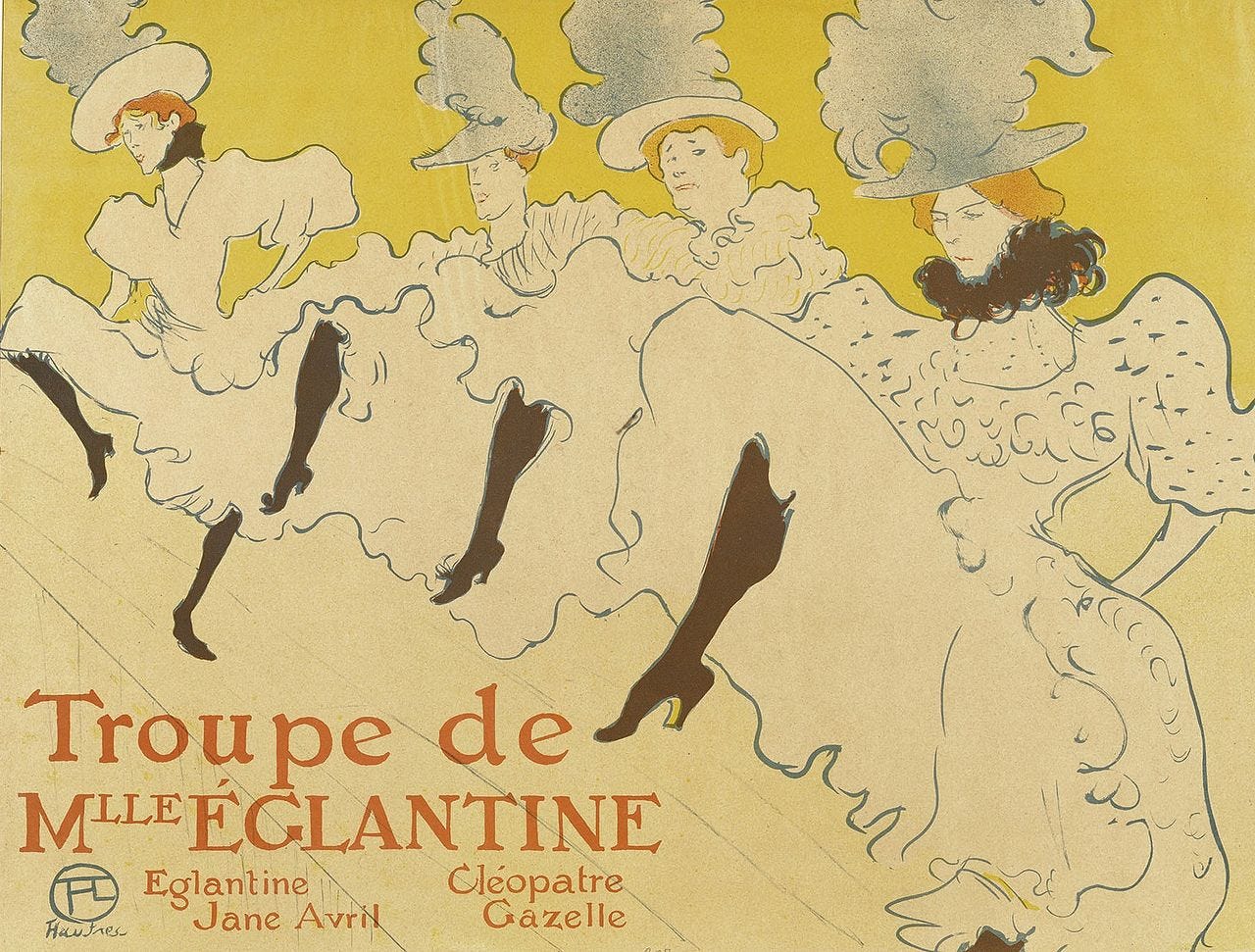

Such cultural incorporations are classic Galliano. He has long been “obsessed with the eighteenth century”, and especially France, as seen by Les Incroyables.48 Brassaï, too, had already served as an inspiration, in John Galliano Hairclips (A/W 1988-89), for Julien d’Ys plastic headdresses in the Black Show (A/W 1994-5) and John Galliano Ready-to-Wear (A/W 2007-8).49 Indeed, the fin-de-siècle pervades Galliano’s fashion fantasies almost as much as the eighteenth century, exemplified by Dior Haute Couture The Edwardian Raj Princesses chez Dior or Mata Hari (A/W 1997-8), “drawn from a combination of strong female heroines including Indian princesses, Sarah Bernhardt, Isadora Duncan, Alphonsa Mucha/Gustav Klimt beauties, Toulouse-Lautrec’s Jane Avril (La Goulou) and the infamous spy Mata Hari.”50

The last important precedent for this collection is Dior Haute Couture Les Clochards or Homeless (S/S 2000). According to Galliano, the collection was based on “the people I came across when I was jogging in the morning around the Seine. Amazing people, proud people, who’d possibly chosen to live like that, who knows?”51 There were deconstructed, torn and shredded dresses, models dressed like tramps, lunatics in Chaplin-style makeup and clothing, and a final phase based on the paintings of Egon Schiele. The collection was immediately controversial, criticised by mental illness and homelessness charities, but Galliano was unrepentant. In fact, he did not understand the criticism at all—creation for him has always been an act of glorification, not parody or ill-thought-out imitation. In the Artisanal Collection, he has resurrected Les Clochards, immortalised them, and proved to the critics of that 2000 Dior collection that everything is worth glorifying through fashion, art and poetry.

Like Artaud, Galliano establishes a theatre where there is “no gap between life and theatre”, foregoing the stage and the separation between the audience and the models. The mise-en-scène evokes an idea of Paris more true than the physical location of Paris—Artaud’s ‘double’ manifesting through Galliano’s creative genius.

b. Bakhtin, Dionysus and the universal ‘double.’

Such a setting, and such a theme, recalls Artaud’s idea of what works are to be staged under the Theatre of Cruelty. Rather than performing written plays, instead the director will stage myth-like themes, “universal, cosmic, performed according to the most ancient texts taken from Mexican, Hindu, Judaic and Iranian cosmogonies, among others.”52 In presenting a universal image of Paris and its underbelly, Galliano does exactly that. Though he intended for there to be some underlying plot, that of vampires ‘having to get back before the stroke of midnight’, the fantasy of this collection is not a story in a linear sense, but a universal, cyclical story, representing the primordial nature of man. As long as the earth turns on its axis and the celestial spheres make so great and so sweet a sound, the universal archetypes will remain: the poet and the thief, the sage and the whore, the couturier and the clochard.

In this sense, it is useful to analyse the collection from another perspective, that of Mikhail Bakhtin, the Russian literary theorist. A Bakhtinian reading of the show will assist us in understanding how Galliano’s idea of the fashion show as a fantastical and mythological performance fulfils Artaud’s vision. This comes in two ways:

Bakhtin considers art to be “oriented towards communication”, inherently dialogic.53 Connecting the novel, and literature more generally, to the Socratic tradition, he argues that a text, in its polyphony, tests ideas, undergirding the “notion of the dialogic nature of truth.”54 This applies to a fashion collection, and its show: the runway is a kind of dialogic poetry in communication with other designers, the critics, the customers and the wider world. So expounds Miranda Priestly in The Devil Wears Prada’s famous ‘cerulean sweater speech’—nobody can “make a choice that exempts them from the fashion industry”, since everything we wear trickles down from the poetic creation of the couturier. This innate intertextuality of the mode of fashion, which draws in innumerable influences, allows us to interrogate, through them, the meaning of a collection, and find within it all its universal aspects.

Bakhtin’s other important conception is that of the carnivalesque, “life turned inside out… monde à l’envers”, where there is “no division into performers and spectators”, the ordinary laws are suspended, and hierarchy is no more, allowing for a “a new mode of interrelationship between individuals.”55 This inversion of the norm allows for a dialogic examination of the truth, and represents “the pathos of shifts and changes, of death and renewal” at the heart of the primordial tradition of the carnival, but also at the heart of everything.56 The fashion show can also be understood in this sense, since it is a timeless snapshot of how the clothes displayed will be worn, interpreted and reinterpreted from then on. It is also inherently propositional, challenging the rest of the world to receive its designs. Bakhtin highlights in particular a poetic descendant of the Socratic dialogue, ‘the dialogue of the dead’, “in which people and ideas separated by centuries collide with one another on the dialogic plane.”57 Is this not exactly what the Artisanal Collection is? An intertextual, dialogic challenge to all of fashion, and art, before and after it? A moment in suspended time, wherein the historic characters of eternal Paris convey the truth of the ‘City of Light’, that is, what lies under its glossy surface?

Through Bakhtin, we can understand the ‘cosmic truths’ that abound in the Artisanal Collection, fulfilling Artaud’s pledge to forego script and dialogue in favour of myth-like themes. Galliano’s image of Paris is mythical, yet true, varied, yet coherent, and intertextual, yet independent. Not only does he engage with Paris’ historical and cultural past, but he also engages with haute couture’s past, and that of clothing in general.58 The show itself was a carnivalesque moment.

We see, then, that the ideas of Bakhtin and Artaud have some cross over. Another curious similarity can be found in Bakhtin’s concept of the ‘laughing aspect’, wherein “everything has its parody, that is, its laughing aspect, for everything is reborn and renewed through death.”59 Some resemblance comes in Artaud’s ‘double’ and his belief in the necessity of both ‘seriousness’ and ‘humour’. Humour, after all, is merely truth by other means. The “physical, anarchic dissolving power”60 of poetry, theatre and literature, more broadly, permits an interrogation of the subject matter in relation to the primordial myths and traditions underlying it.

That certain profanities occur in Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty is unsurprising, too. It is in Bakhtin’s timeless carnivalesque that profanation occurs, fostering the grotesque, parody and subversion. Both Bakhtin’s carnivalesque and Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty exist on the threshold, where uncertainty reigns, but makes more distinct and tangible the universal. Thus a major criticism of Les Clochards (S/S 2000), that the collection parodied “a matter of life and death,”61 is fundamentally idiotic, and misunderstands art entirely. Matters of life and death are precisely the topics to depict!

Such matters recall the religious character of theatre—a factor utterly essential in attracting Artaud to theatre. A major inspiration for Artaud was the Balinese theatre he encountered at the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition, which had “something of the ceremonial quality of a religious rite.”62 Artaud viewed this show as “like a profane ritual. It has the solemnity of a holy ritual—the hieratic costumes give each actor a kind of dual body, dual limbs—and in his costume, the stiff stilted artist seems merely his own effigy.”63

This mixture of sacred and profane harks back to the development of theatre in the first place. Aristotle attributes the origin of tragedy to the “leaders of dithyramb”,64 which was a form of choral hymn to Dionysus. A chorus of men or boys, dressed as satyrs (hence τραγῳδία tragoidia ‘tragedy’ being derived from τράγος tragos ‘goat’ and ᾠδή oide ‘song’), would sing and dance together at religious festivals such as the Athenian Dionysia. Later, the Dionysia would come to host plays, staged as a competition between playwrights, with the first play apparently staged by the poet Thespis (hence ‘thespian’). Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides were its most famous winners.

In theatre’s origin as religious rites, we return to the carnivalesque and Theatre of Cruelty. Essential to all religions is the renewal of these rites, during which the homo religiosus enters into ‘sacred time’. As Eliade writes, “every religious festival… represents the reactualisation of a sacred event that took place in a mythical past “in the beginning”.”65 It is little wonder, then, that in order to access this universal, cosmic time, festivals took on a carnivalesque character, wherein the laws and norms of the current, mundane time were suspended, such as in the Roman Saturnalia. Thus comes “carnivalistic mésalliances… [that] combine the sacred with the profane.”66 As the festival’s progeny, theatre adopts the carnivalesque character, becoming a temporary respite from quotidian life and, indeed, a mode for the pursuit of universals. The Theatre of Cruelty exists in this setting, as it seeks the ‘double.’

Artaud seems, then, to embrace a more Dionysian understanding of theatre, going in the opposite direction to Nietzsche’s Euripides. The crucial divergence of Artaud from Bakhtin’s thinking is in Artaud’s rejection, or, at the very least, sidelining, of dialogue. Artaud wishes to prove that “metaphysics… [can] enter the mind through the body.”67 Yet, undoubtedly, some traces of the Apollonian do remain, such as in his ideas of the ‘double’ and ‘cruelty’, which both to some extent inhabit the ‘dream-reality’ that Nietzsche describes. Indeed, Artaud was all too aware of this fact. As such, in line with his Gnostic interpretation of life, on which I shall elaborate in the third part of this series, he wished equally for a liberation from both the body and the mind and from both the Apollonian and the Dionysian. Ever seeking release from the torturous anguish of life, Artaud envies the tragic Pentheus, and wishes to become him, that is, to be torn limb from limb in a bloodsoaked scene of hysterical madness. Artaud desires a unification of the sacred and the profane in the construction of an ‘intelligent body’, that rejects the transience of ideas and the profanity of the body. It is the Theatre of Cruelty that will construct this ‘intelligent body’, whose vibrations will communicate the ‘double’, that is, the primordial truth, to the pulverised and brutalised audience. Man will be liberated from the satyric state: “beneath the poetry of the texts, there is actual poetry, without form and without text.”68

Thus religion is deeply theatrical and theatre deeply religious, though theatre’s religious character does not require it to explore only explicitly religious themes. The Theatre of Cruelty, directed by “the producer… a kind of organiser of magic, a master of holy ceremonies”,69 is a form of religious ritual, renewing cosmic and universal truths common to us all. Thus, in fulfilling aspects of the Theatre of Cruelty, the Artisanal Collection grips us tightly and shocks us awake. John Galliano’s depiction of Paris through the looking-glass represents that city’s eternity and evokes the ‘cosmic strictness’ and ‘relentless necessity’ of the Theatre of Cruelty, that depicts, as Evola calls them, “realities of a superior, archetypal order, which are shadowed in various ways by symbols and myths… history and superhistory intersect and integrate each other.”70 In this, we observe a divine portraiture—animate Singer Sargents that we recognise with distinct familiarity.

c. Flesh, mess and porcelain

Artaud’s relationship to the grotesque is oft mischaracterised. Undoubtedly affected by perceptions of Artaud’s personal behaviour, the position of the grotesque in the Theatre of Cruelty is generally overemphasised, being the most ostensibly bizarre feature of Artaud’s aesthetic manifesto. It is a major element, but not philosophically central. Rather, it is an important tool for realising Artaud’s vision, that is, the ‘double’, through ‘cruelty’. Shock, horror and the grotesque are subversive tools, designed to “pulverise, mesmerize the audience’s sensibilities, caught in the drama as if in a vortex of higher forces.”71 The Artisanal Collection exhibits such grotesqueries, or, as Artaud calls them and broadly any other experimentations with the senses, discords. These discords are multi-sensory, and are successfully united in the Artisanal Collection. Just as the collection’s mise-en-scène echoes Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, so too do the ‘looks’ themselves.

The collection’s looks can be split into thematic categories, deriving from the appearances of the female models, who dominate the collection. The male characters are less varied, except for a few unique looks, such as Leon Dame in the opening, the ‘mad hatter’ (24), or the ‘man with the umbrella’ (33). Generally the male looks seem to represent male prostitutes, the ladies’ clientele, or the sorts of thieves, ruffians and rogues that inhabit all cities’ underbellies. Please note that I will be examining the clothes on an aesthetic basis, not a technical basis, on which I am less qualified to comment. Please see Maison Margiela’s press release for more detail.

Leon Dame’s opening serves as a proem, outlining the aesthetic principles of the collection. Half-naked, he wears a flat cap and a corset that tightens his waist and widens his hips.72 First, his nakedness, in the conservative context of old Paris, is striking and provocative. To clothe or not to clothe are equally expressive decisions in fashion, just like silence and sound in music. The wisps of chest hair and his gaunt model-build unsettle. His boyishness, exemplified by the baker boy hat, is coupled with a sense of despair. He is old before his time—the corroding effect of the streets. Flesh being on display is a key theme of the collection. Second, his corset shapes his body in unnatural ways. The poverty of the streets exists always with excess. Radical body proportions are an essential aspect of this collection, accentuating or inverting sex differences between the male and female models.

Looks 2-18 are the ‘ladies of the night’ at their most seductive, accompanied by their ghostly customers. Translucent black dresses reveal their flesh and breasts, both seen, to attract attention, and covered, to signal unavailability, at least until a fee is paid. Corsets (and stays) again dominate, presenting hourglass figures, a traditionally conventional beauty standard, in an unconventional, distorted way. On their heads, what seem like hats, in the style of Toulouse-Lautrec’s depictions of Jane Avril and the can-can, are actually ‘frizzy discs of hair’, crafted by the stylist Duffy. The accessory is melded with the model herself, in a sort of minimalistic Cronenbergism. We might ask: what is human and what is cosmetic? Similar to this is the use of the merkin, a pubic wig, which explicitly develops on Dame’s body hair. Merkins originated for personal hygiene reasons and were particularly used by prostitutes to avoid public lice or syphilis. Their sexuality is on display, yet it is artificial and grotesque.

Looks 19 and 21 might be termed ‘spider silhouettes’, since the models wear lace skirts and oversized white foam jackets, with spiderweb designs draped all over. The webs seem to be constructed from their torn stockings. The desperation of the streets has brought about ad-hoc creation. Again, their accentuated features are freakish. If this is Hell, are these those sinful body parts punished by a Dantean penalty?

Looks 22-27 comprise the ‘decaying ladies’, accompanied by the ‘mad hatter’ (their pimp?). Galliano utilises boiled wool, torn stockings and porcelain-imitation leather made by Robert Mercier, which reminds us of toilets and thus defecation. The ‘porcelain bibs’ echo the fastening points where porcelain doll heads were affixed to their cloth bodies, evoking fragility and possibly subverting the historic popularity of porcelain wares in Paris, particularly in the Chinoiserie style. Again, these characters seem to have constructed their own outfits out of the squalor of the slums. Always in decay, they must continue on, and clothe themselves as best they can in garbage, debris and refuse. The astonishing technique of ‘caisetting’ forms, in looks 26 and 27, dresses out of “silk organza and crin… ridged to resemble corrugated cardboard.”73 On their heads are mushroom hats, growing from the wastage and squalid conditions of subterranean Paris.

Looks 28, 29 and 31 press on with the fungal aesthetic. The women are now themselves mushrooms, covered all over in a Fauvist mould. Their covered faces hide their identities. The biological horror of the outfits represent the biological horror of a life of prostitution, at all times vulnerable to the venereal diseases carried by predatory clients.

Looks 32-40, split more evenly between men and women, comprise deconstructed suits and coats, in a carnivalesque formality. They wear goggles and long silicon gloves. Look 39’s dress is covered by see-through polka-dots, the work of the moths. Are these characters doctors, come to administer their cures to the polluted souls of Paris, or even amputate some limbs? Or are they businessmen, who, venturing into the slums in sadistic glee, must, out of disgust, wear protection against the threatening viscera of Paris?

The final looks, 41-44, extrapolate this further. Now come the aristocrats of the ancien régime, with their curly wig-like golden hair, extravagant robes and elaborate make-up. Here is the style of ‘Le Grand Siècle’—straight from Versailles—combined with the characteristically French blue and white striping of the marinière, which Coco Chanel popularised in the fashion world. The final two models bring back those silicon coverings, culminating in Gwendoline Christie’s “silicone-coated, white silk taffeta dress”.74 The red soles of the Louboutins recall the red heels of royalty, popularised in France by Louis XIV’s brother Philippe d’Orléans. Are these models perverted aristocrats plunging into the sewers of Paris, like Prince Albert Victor, a Jack the Ripper suspect, was rumoured to do? Or has the revolution toppled them, now needing to beg and sell their bodies on the streets? Their doll-like appearances set them apart from the others. Pat McGrath’s astounding make-up develops throughout the show, going from a translucent damp skin to this colourful, almost Elizabethan, look. As Baroque dolls, they may decay like the others, or even shatter to pieces, but are simultaneously perfect in all their vulnerability.

In this Artisanal Collection, Galliano has exhibited the grotesque in an Artaudian spectacle. These grotesqueries existed alongside beauty, and astonishingly innovative techniques. The clothes, and models wearing them, are a vortex of ideas, interrogating class and social position, sexuality, vulgarity and disgust. In doing so, Galliano mesmerised the audience’s sensibilities—‘every character being typified to the limit’—as Artaud had wished for his Theatre of Cruelty.

d. The choreography of cruelty

Du temps que la Nature en sa verve puissante

Concevait chaque jour des enfants monstrueux,

J'eusse aimé vivre auprès d'une jeune géante,

Comme aux pieds d'une reine un chat voluptueux.

J'eusse aimé voir son corps fleurir avec son âme

Et grandir librement dans ses terribles jeux;

Deviner si son coeur couve une sombre flamme

Aux humides brouillards qui nagent dans ses yeux;

At the time when Nature with a lusty spirit

Was conceiving monstrous children each day,

I should have liked to live near a young giantess,

Like a voluptuous cat at the feet of a queen.

I should have liked to see her soul and body thrive

And grow without restraint in her terrible games;

To divine by the mist swimming within her eyes

If her heart harbored a smoldering flame…

Baudelaire, La Géante (tr. Aggeler).

In the movements of the Artisanal Collection, Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty incarnates. Its choreography, created by movement director Pat Boguslawksi, was above all theatre. Each model played a character developed by Galliano and Boguslawski.75 Each had a unique personality and gait. These characters were neither isolated from each other, nor from the audience of spectators. The reality of the corsets, prostheses, clothes and heels created a bizarre procession, as they paced through le tripot:

Sprinting out the mist, again Leon Dame characterises the collection to come. Having fled some night-predator, he catches his breath, then begins. He shows off his half-naked body, solicits the audience, contorts himself, stares at them, begs and guilts them, then continues on into the bowels of Paris. Out stream the ladies of the night, swaying their hips and making suggestions. They stand, stop, and show off their figures. Some cross their arms, protecting their body from the harshness of their profession. The men who shadow them skulk, hide beneath their grey coats, confront the audience.

The ‘spider silhouettes’ and ‘decaying ladies’ struggle with their outsized proportions. They sway, too, but at robotic, unbalanced angles; like faulty dolls, their arms twitch and flap—so weakened by the streets they cannot control their own bodies. Next the ‘fungi’, thin as a wisp, translucent, barely there, swing with their dangling dresses. The ‘goggled’ ones stride with explicit purpose, intentional gait and sadistic detachment. Their suits are the work of tailors and their silicon gloves industrial products, putting them at an immediate advantage over the waifs they hunt.

Last, at last, the historic aristocrats, Paris’ former governing class, traipse through the underground bar. These broken dolls are anatomically damaged, yet aesthetically as perfect as they ever were—as when they were powdered and perfumed at Versailles. The show is crowned, in the final position, by la géante—Gwendoline Christie, towering over the audience, displaying herself proudly to the Parisian underbelly. She balances effectively en pointe; the malformed heels accentutate her height, just as the corset and dress accentuate her proportions.

As all these characters flow through the sewer of Paris, the tripot becomes like a great pipe filled with the squalid, invisible excrement that the polite, well-to-do people of the surface ignore. Galliano creates an uncomfortable beauty, unsettling in its brilliance, exactly as Artaud had desired a hundred years before. There may not have been groans and screams, but there was rhythm, and the magic beauty of the costumes, and new surprising objects, masks, characters typified to the limit, grown as tall as gigantic puppets, appearing as so many shafts of light, with no moves wasted. The human body was raised to the dignity of signs—metaphysics was made to enter the mind through the body.76

Barber, S.: Antonin Artaud: blows and bombs (1994), 13, quoting Theatre of Cruelty, 1947, Collected Works, XIII, 1974, 118.

Artaud in Melzer 1966, 133, quoted in Morris, 79, and Artaud Collected Works 2, p. 37.

Barber 1994 Antonin Artaud: Blows and Bombs, 5.

Sontag 1980 42.

Barber 1994, 5. Other references to those influenced see same chapter.

And indeed, Artaud in his first manifesto wished to perform “one of the Marquis de Sade’s tales”. TD, 71.

Morris, 75, in: Rose, Mark. The Actor and His Double: Mime and Movement for the Theatre of Cruelty (1983), p. 279.

Ezra Pound, ABC of Reading, 34.

Artaud, in: Sontag 1980, 19.

Sontag 1980, 18.

TD, 16-17.

TD, 60: “Theatre of Cruelty proposes to resort to mass theatre, thereby rediscovering a little of the poetry in the ferment of great, agitated crowds hurled against one another, sensations only too rare nowadays, when masses of holiday crowds throng the streets.”

TD, 30.

TD, 4.

https://x.com/Daily_Proust/status/1793339794124140809

Letter 13: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Moral_letters_to_Lucilius/Letter_13

After writing this, I discovered a similar sentiment elsewhere: “Art transfigures life, moves it into higher, as yet unlived, possibilities. These do not hover “above” life; rather, they awaken life anew out of itself and make it vigilant. For “only through magic does life remain awake” (Stefan George, Das Neue Reich, p. 75).” — Heidegger - Nietzsche Vol 3 The Will to Power as Knowledge and as Metaphysics. Relates somewhat to Seymour Bernstein’s thoughts in OTSI (and perhaps is a better synthesis):

Barber 1994, 7; then, Surrealist Manifesto.

Morris, 49, quoting Artaud’s Letter to Jean Paulhan.

TD, 34.

TD, 73.

TD, 74.

Ibid.

TD, 73.

TD, 63.

TD, 70.

TD, 72.

TD, 59.

TD, 66.

TD, 90.

Ibid.

Ibid.,

Ibid., 70.

TD, 68.

TD, 90-1.

TD, 91.

TD, 69.

TD, 88.

G&K, 233.

G&K, 70.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=J5t41SySiP4

TD, 88.

TD, 4.

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2019/oct/08/city-of-light-brassai-paris-in-pictures-photography. https://archive.is/39Q8u.

I use this term rather than Belle Époque because it seems to me to be more accurate. There may have been material riches, but the moral decadence was that period’s characterising feature.

G&K, 56.

Spectacular Fashion, 56, 101, 317.

Ibid., 153-4. Other fin-de-siècle-influenced collections include Dior Haute Couture In a Boudoir Mood (S/S 1998), John Galliano Ready-to-Wear (S/S 2004), John Galliano Ready-to-Wear (A/W 2007-8) and John Galliano Ready-to-Wear (A/W 2011-12).

High and Low, 45:48.

see n. 35.

Bakhtin, M., Iswolsky, H. (tr.): Rabelais and His World (1968; orig. 1965), viii.

Bakhtin, M., Emerson, C. (ed. and tr.): Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics (1984; orig. 1963), 110.

Bakhtin 1984, 122; ibid.; ibid., 123.

Bakhtin 1984, 124.

Bakhtin 1984, 112.

Maison Margiela Show Explained — This is a fantastic video that focusses on the clothing in much more detail than I am able to, especially Galliano’s engagement with previous collections and items of Maison Margiela.

Bakhtin 1984, 127.

TD, 29.

G&K, 391.

Sontag 1980, 54.

TD, 42.

Aristotle, Poetics 1449a10; Loeb (Halliwell) translation.

Elaide, M. The Sacred and the Profane, 68-9. The uniqueness of Christian rites, writes Eliade, is that “Christian liturgy unfolds in a historical time sanctified by the incarnation of the Son of God.” (p. 72)

Bakhtin 1984, 123.

TD, 70.

See Nietzsche, Birth of Tragedy; and, Goodall, J. Artaud and the Gnostic Drama (1994), 38; TD, 78. See also Jannarone, K. Artaud and his Doubles (2010), 62ff. on Nietzsche and also Baker, G. “Nietzsche, Artaud and Tragic Politics” Comparative Literature Vol. 55 No. 1 (2003), 1-23.

TD, 43.

Evola, J.: The Mystery of the Grail, 10-11.

See n. 25.

These corsets are actually also prostheses, intended not just to shrink the waist but widen the hips.

Maison Margiela press release, 3.

https://crfashionbook.com/movement-director-pat-boguslawski-breaks-down-the-viral-maison-margiela-runway-walk/

https://www.interviewmagazine.com/fashion/meet-pat-boguslawski-the-movement-director-behind-margielas-viral-couture-show; https://www.papermag.com/maison-margiela-pat-boguslawski.

All of these descriptions are from the Theatre of Cruelty section above, though not quoted directly in order.