Matter out of Madness I: Incipit

"Violent, concentrated action is like lyricism" - Antonin Artaud

Pluviôse, irrité contre la ville entière,

De son urne à grands flots verse un froid ténébreux

Aux pâles habitants du voisin cimetière

Et la mortalité sur les faubourgs brumeux.

January, irritated with the whole city,

Pours from his urn great waves of gloomy cold

On the pale occupants of the nearby graveyard

And death upon the foggy slums.

Baudelaire, Spleen (tr. Aggeler)1

…and out of that fog swelled a silhouette… Leon Dame… a psychopomp… of brides… of youths.. of the old who had borne much… souls stained with recent tears…2

6 Pluviôse (25th January) saw John Galliano, the fallen angel of fashion, unleash upon the streets of Paris the underworld itself. His models, processing in a Gehennic garb, had ris’n from a hellish squalor to a vivid beauty. The light of 2024’s first full moon—indistinguishable from the myriad specks of Parisian street-light—illuminated them.

What gushing madness, pouring forth, from the throat of the earth! What streaming shades of fabric, lancing limbs and veiled faces! At last! The cadaverous dead were displayed to the world—no longer in the shadows. In their last gasps such euphoria arose: a glorious rigor mortis!

At the violet hour, John Galliano conjured a Nekyia. The lost souls of Paris, the lowest of the dead, performed a carnivalesque drama—a theatre of cruelty.

Matter out of Madness

What is genius but temporarily ordered madness?3 In previous writings, I have discussed the lightning strike that is poetic inspiration—that divine madness of sublimity. The purpose of this essay, and the series to come, is to understand this phenomenon through real-life examples of unconventional genius, to answer the question: how was it possible that certain artists or poets, whose own lives were in utter disarray, were able to create art so brilliant, so coherent and so sublime? How did they make matter out of madness?

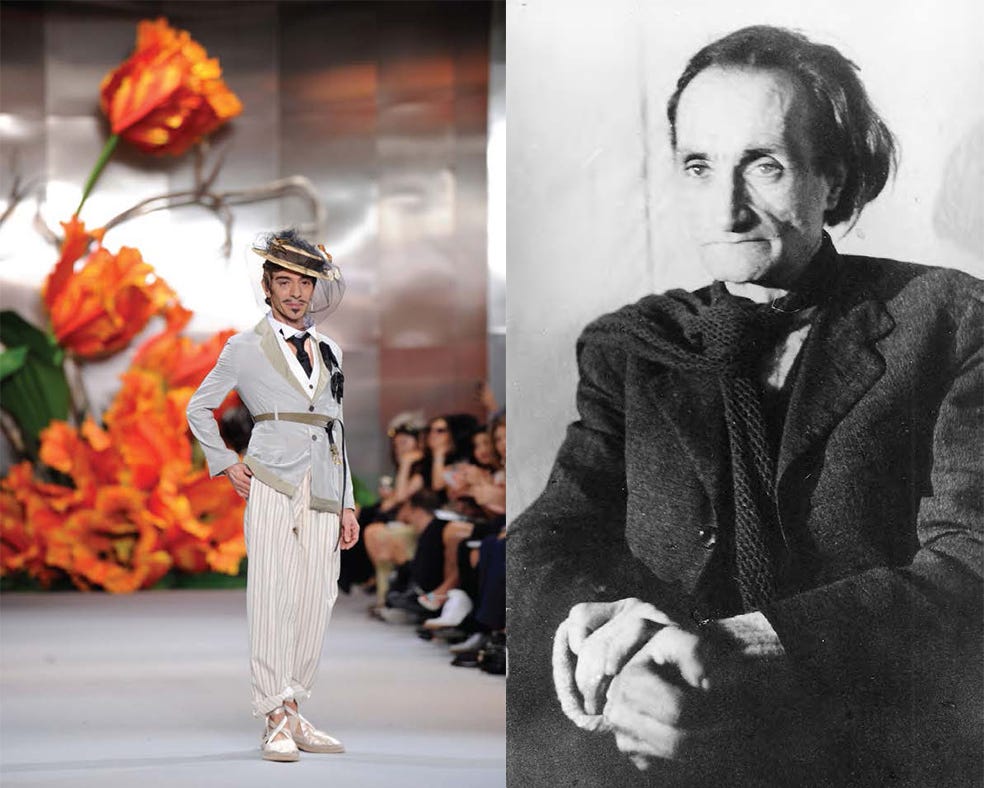

Two poetic case studies lie at the centre of my investigation. First, the revolutionary designer John Galliano. What force but anarchy inspired him? What force but madness resurrected haute couture? What cruel force created and destroyed him? Perhaps more than any other designer, Galliano has the ability to harness chaos, and create great works of beauty ex nihilo, or, rather, ex chao. Second, the dramatic visionary Antonin Artaud, whose Theatre of Cruelty sought to “pulverise, mesmerize the audience’s sensibilities” with “shouts, groans, apparitions, surprise, [and] dramatic moments of all kinds.”4 Was it insanity that incited his crusade for a new theatre? How could such extreme personal tumult lead to such a brilliant legacy? Was he a failure in life? Were his words made flesh?

On the battlefield of each man’s mind a constant, mental Chaoskampf was waged. A chaos that has the power to create and destroy. I shall examine these two Chaoskämpfe in three contexts, forming three essays. The current essay will explore Galliano and Artaud’s psychological and creative profiles, the second will execute a close reading of Galliano’s Maison Margiela Artisanal Collection 2024 as fulfilment of Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty and the third will investigate unconventional genius through the lens of Artaud’s concept of ‘Cruelty’.

Throughout, my main anchor will be the Artisanal Collection, which represents the culmination of Galliano’s creative power and artistic history, especially important in the context of his triumphal return to haute couture as creative director of Maison Margiela. I would recommend watching the fashion show itself, for reference purposes (see this footnote).5 My ambition, in more particular terms, is to understand why this collection was so sublime, and from where such inspiration came. In doing so, I hope this tripytch of essays will elaborate on, and be a successor series to, my previous series On the Sublime. So, how was Galliano able to divide the light from the darkness?

Let there be light

“The ritual of dressing is a composition of the self. With the body as our canvas, we build an exterior expressive of the interior: a form of emotion.”

—Maison Margiela Artisanal Collection 2024 Press Release.

The word fashion derives, through Anglo-Norman and Old French, from the Latin verb facio—to do, to make. Though in English the word has come to be more associated with trend and style, at its heart fashion is creation. Such an idea is multiple in sense. The couturier creates when he designs the piece; the atelier hands create when they fabricate the piece; the customer creates when she wears the piece. Each phase of creation contributes to the final piece. Each phase is a form of expression.

Such collaboration necessarily engenders limitation. The customer might require of the couturier a certain fit, to cohere with her measurements, or with the tone of the event at which she intends to wear the piece. The atelier hands and the fashion house might have techniques, styles or aesthetics traditional to them that require the couturier or customer to tailor their vision. Most importantly, of course, the couturier issues the commands that place into order the creation of the individual piece, from beginning to end, and the collection of which it is a part, as an aesthetic whole.

Though these are limitations, they do not, in fact, confine the participants, and certainly not the couturier, to a creative prison. Rather, they act as lens of interpretation, developing the piece or collection, and unlocking a creative space hitherto inaccessible. This is the freedom of limitation—if we impose standards upon ourselves, we prompt innovation, and raise standards. It is primarily the genius of the couturier that directs this process, varying in extent depending on the designer. John Galliano’s process is unique to his soul—he prefers cutting on the bias to cutting on the grain, just as a poet might prefer pentameter to tetrameter.

The result of this thinking is a conceptually expansive view of fashion as a creative medium. In this way, it becomes no different to poetry; indeed, the focus of the Artisanal Collection was the art itself—poetry, tinged with the brilliant madness of John Galliano. So let us ask: what is poetry, anyway? What is poetry, is poetry. Good poetry, that is, true poetry, is poetry. Poetry is known and observed, not defined. And yet, our postmodern time has deconstructed what we all intrinsically know, so that nothing, anymore, is poetry. This cannot last; for life struggles to defend itself without poetry. Poetry represents life; and, though it is definitionally false, it is truer to life in its untruth.

We must embrace an unlimited view of literature—a view that extends literature to such a degree that it is encompassed in its entirety by aesthetics—a total aesthetics. Rapidly, in this mode, life and literature become utterly indistinguishable. The objective becomes to make everything not only beautiful but also intellectually beautiful—to a certain degree the same thing—that is, to attempt to transcend the mundanity of modern life in its entirety. Yet, rather than escaping above and beyond, we must strive towards a precipitation of the ideal—to make God noise in the street: platonic and peripatetic. From there we arrive at the intersection of literature and of life itself. The formlessness of its definition inverts literature, and transforms it into all things.

Poetry without words is still poetry—an expression of reality in irreality. It is Artaud’s ‘double’. It is Herzog’s ‘ecstatic truth’. It is the sign, the symbol. It is Mallarmé’s suggestiveness. Mallarmé’s imitation. Mallarmé’s dream.6 Poetry is just as much a lyric, as it is a painting, as it is a song, as it is a film, as it is a flower, as it is a vivid, flashing dream. Many poems layer upon themselves multiple forms of medium: among others, Liszt, Strauss and Scriabin wrote tone poems—les poèmes de l’extase—and did not Gainsbourg set Verlaine and Prévert to sound? And how rich are the brush-strokes of Monet, or Renoir, that seem more alive than life itself? So why not fashion, and more intensely, haute couture? Just as we analyse poetry, we must analyse haute couture. But first, we must understand the poets themselves.

Parallel Lives

“Whether they admit it or not, whether a conscious or unconscious act, at heart audiences are searching for a poetic state of mind, a transcendent condition by means of love, crime, drugs, war or insurrection.”—Antonin Artaud.7

“How did logic arise in the human head? Doubtless, out of illogic…” —Nietzsche.8

Juan Carlos Antonio Galliano-Guillén was born on the 28th November 1960 in Gibraltar. His father was Gibraltarian and his mother was Spanish. At six, his family moved to South London, where he grew up. Raised a strict Catholic, John, as he was called in England, always remained deeply influenced by his Gibraltarian-Andalusian roots. On the occasion of his first communion, “‘[he] arrived in this dazzling white suit, bedecked with rosary beads and gold chains and ribbons with all the saints on.’ The other boys were in their conservative school uniforms.”9 Such extravagance and aesthetic idiosyncrasy continues, to this day, to undergird his approach to fashion.

In 1981 a passion for art, and later fashion illustration, led Galliano to win a place at Saint Martin’s School of Art. During this period at Saint Martin’s, we can identify early inspirations. The New Romantic movement, with its post-punk, glam rock and Romantic period inspirations, was at its apogee. Vivienne Westwood was the pioneer of the British fashion scene, releasing collections inspired by 18th century pirates and the French Revolutionary era decadence of the Incroyables.10 Artists like David Bowie and Adam and the Ants, among others, often at the encouragement of Malcolm McLaren, Westwood’s husband, began to embrace a more androgynous and ostentatious aesthetic. The quiet Catholic boy was mesmerised.

Growing up in such a conservative household, exacerbated by an early realisation of his homosexuality, had made Galliano susceptible to escapism. Being finally free to express his fantasies, he quickly became involved in the London club scene, discovering drink and drugs in the wild world of 1980s Soho and rubbing shoulders with Boy George and Billy Idol in his favourite club Taboo.11 He began to dress flamboyantly, experimenting and associating with radical creatives, while fostering a reputation for being a destructive, black-out drunk.

While at Saint Martin’s, Galliano took a part-time job at the National Theatre, dressing such actors as Dame Judi Dench, Sir Ralph Richardson and Zoe Wanamaker. He said of the experience: the actors “taught me very much about bodies and clothes. And how they commanded their space… it helped shape my view of drama, of clothing, of costume — the way people dress.”12 Around the same time, the film historian Kevin Brownlow restored Abel Gance’s 1927 magnum opus Napoleon, notably starring an ambitious Antonin Artaud as Jean-Paul Marat. Galliano was immediately taken by it; thus began an obsession with France, particularly of the 18th and 19th centuries.13 He also spent some time learning tailoring at Tommy Nutter on Savile Row. Within such a maelstrom of personal and aesthetic development, Galliano began to formulate his 1984 graduating collection: Les Incroyables.

Les Incroyables (1984) was inspired by the aforementioned French aristocratic movement who, after the Reign of Terror in the French Revolution, took to a life of decadence and debauchery, wearing “frilly clothing to flaunt social and political disregard.”14 It’s not entirely clear whether Galliano was aware of Westwood’s use of the Incroyables’ style in her Pirate collection (which was initially based on them, but changed to pirates, “another form of punk”,15 at Malcolm McLaren’s urging), though we know Galliano was a Westwood fanatic: “Vivienne’s work during the punk and new romantic periods defined the era.”16 Apparently having discovered the movement during his research at the fashion archives of V&A, Galliano immediately resonated with the idea, feeling that it matched his own lifestyle at the time: “I was looking like this down-and-out French tramp… Living it, breathing it. Drawing by candlelight… I could just imagine these fantastic creatures marching, running across the wet shiny cobblestones of Paris.”17 What better subject matter to bring to life than his own daydreams?

The collection was a triumphant success: “There were billowing eighteenth-century blouses with frilly neckerchiefs and jodhpurs with knee-high black riding boots; over-sized trenches in pale grey and ivory with shoulders down by the elbows; huge kimono-like coats over soft, ample pajamas; deconstructed black frock coats with waistcoats and fitted white shirts with high collars tied up in a poofy bow.”18 Joan Burstein at Browns bought the entire collection, and Galliano’s career exploded into life.

Antoine Marie Joseph Paul Artaud was born on the 4th September 1896 in Marseille. His father was half-French half-Greek and his mother was Greek, from Smyrna. At five, he contracted meningitis, which marked the beginning of a life of severe sickness. Raised a strict Catholic, Antonin, as he was called in dimunitive form, grew up in a thick web of familial constriction: his paternal and maternal grandmothers were sisters, he had a large extended family, and many siblings. Like Galliano, his father was a strict Mediterranean conservative, who expected him to be a man of “honour.. serious probity… duty… who, when the time came to follow in their father’s footsteps, knew how to be bosses in every noble sense of the word.”19 Neither Galliano nor Artaud followed in their fathers’ footsteps.

In opposition to the ‘strangulation’ he identified with his father was the affectionate intensity he found in his mother. Through her he knew a mystical Catholicism: “the young Artaud devoutly prayed for several hours a day.”20 For the rest of his life he remained religiously intense, leading to his “[theorising] theatre as a religious, holy experience.”21 At school, Artaud discovered the works of Edgar Allan Poe, Arthur Rimbaud and Stéphane Mallarmé, whose pioneering (Symbolist) styles prefigured the Modernist and Surrealist movements. Artaud soon became a poet.

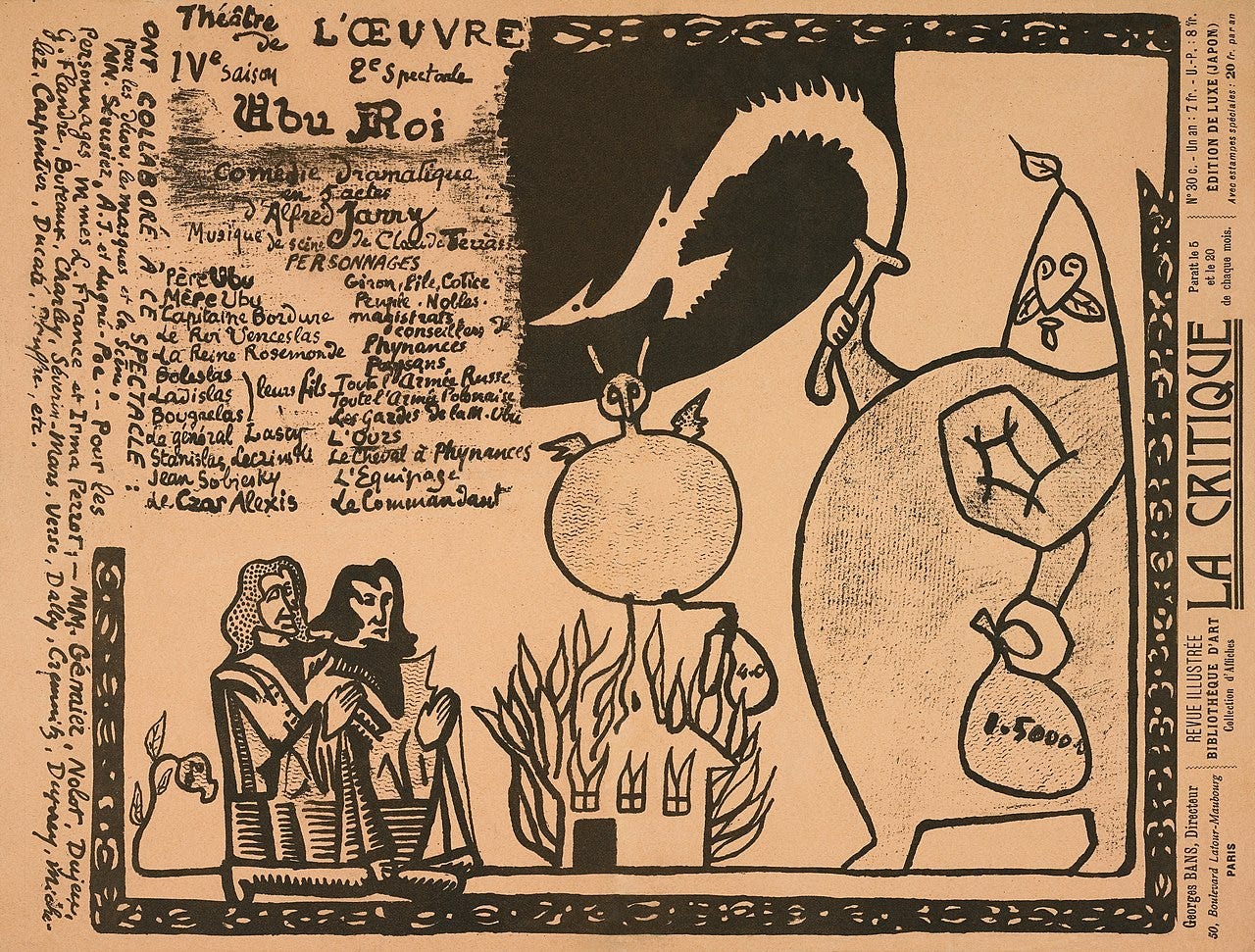

In 1914 Artaud had the first of his many breakdowns, and burned all his works.22 His parents committed him to a number of sanatoriums, where he rediscovered his creativity, though, while there, a doctor “prescribed him morphine and laudanum, solidifying what became Artaud’s lifelong addiction to opiates.”23 The same psychiatrist, Dr Joseph Grasset, saw Artaud’s mental illness as a “result [of] consanguineal kinships and […] indulgence in religious excesses.”24 In 1920 Artaud was transferred to the care of Dr. Édouard Toulouse in Villejuif, Paris, who focussed on the relationship between artistic genius and psychiatric diagnoses.”25 Toulouse encouraged his intellectual growth, making him managing editor of his own journal Demain and connecting him with Lugné-Poe, the famous director of Theatre de l’Œuvre, made infamous for premiering Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi in 1896. Ubu Roi was a scandalous, obscene, absurdist parody of Macbeth, which W. B. Yeats, present on opening night, worried signalled the abandonment of romantically-inclined, ‘high’ modernism, for “the Savage God.”26 Listen to Debussy’s L’Après-midi d'un faune, then turn to Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du printemps, for reference.

After some minor success with Lugné-Poe, Artaud was invited to join Charles Dullin’s troupe Theatre de l’Atelier, which Artaud described as “both a theatre and a school… whose purpose is to internalize the actor’s performance.”27 Dullin viewed theatre as “a complete art, sufficient unto itself”, that is, “a total theatre in which gesture, mime, colour, music and movement would rival dialogue in importance.”28 The group trained as a commune, on an “intensing training regimen of ‘ten to twelve hours a day’, which included gymnastics, concentration exercises, improvisations, and voice training, with a focus on direction and breath.”29 Artaud was mesmerised, for he had long wished for a theatre “conceived as the achievement of human desires… [rather than] momentary excitement.”30 Dullin also introduced Artaud to East Asian theatre, such as Yuan-era Zaju, Japanese Nō and Balinese plays.

Artaud’s time at Theatre de l’Atelier was largely successful. He appeared in numerous plays, including Jean Cocteau’s Antigone (1922), with its sets designed by Picasso and costumes by Coco Chanel, Calderón de la Barca’s La vie est un songe (1922) and, Jacinto Grau’s Monsieur de Pygmalion (1923), his highlight role. Even with all this success, which also manifested in his contributions to set design, costuming and make-up, Artaud’s eccentricity eventually began to show. During a rehearsal of Arnoux’s Huon de Bordeaux (1923), playing the Emperor Charlemagne, he “came onto the stage on all fours and crawled to the throne.”31 Such madness always characterised him: Dullin dropped him from the cast, and they parted ways.

The rest of the 1920s for Artaud was defined by experimentation. He became a film-actor, debuting in Autant-Lara’s short film Fait Divers (1923). He starred in twenty-three films in total, most notably Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927) as Jean-Paul Marat (which so inspired Galliano) and Carl Theodor Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928) as the monk Massieu. A pattern of religious or revolutionary fervour characterised many of his roles. Such radicalism also manifested in a brief fervour for the Surrealist movement. Artaud was heavily influenced by André Breton’s idea of ‘psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express… the actual functioning of thought.”32 He participated as an official member, even editing the third edition of La Révolution Surréaliste (1925). Yet, Surrealism soon required a loyalty to communism that Artaud could not stand. According to Breton, theatre was explicitly bourgeois and Artaud was condemned for only being interested in “a change of the internal conditions of the soul”.33 He was expelled.

For many years Antonin Artaud had sought a metaphysical, higher, more sublime understanding of theatre. This medium was more than ‘make-believe’, but a window into the soul—more true than truth itself. No movement or troupe could satiate him. He had to find the answer himself. He had to be the cult-leader, not a mere follower. Thus came Théâtre Alfred Jarry.

Ex nihilo nihil fit

Fantasy, intensity, fervour: the characteristics of genius? Certainly the pursuit of truth above all. And is not beauty truth and truth beauty? In life, both Galliano and Artaud suffered. Their spirits were double, knowing beauty and its antithesis. Their destructive doppelgangers too often took control, aiming partly at others, but mostly at themselves. Finding reality insufficient, they created; but their creations were just as ephemeral as their satisfaction with them. The black dog hounded them always.

Having launched his career with Les Incroyables, Galliano, with financial backing, formed his own fashion house, John Galliano. He continued developing his radical style: garments inside-out, the wrong-way-round and deconstructed, combined with exotic cultural influences and story-telling. His early collections included Afghanistan Repudiates Western Ideals (S/S 1985), The Ludic Game (A/W 1985-6)—“A Brueghel painting cavorts around the maypole of a village green in Dorset”34—Fallen Angels (S/S 1986), based on post-Revolution France, and Forgotten Innocents (A/W 1986-7). By this point, it became clear that Galliano’s lifestyle was unhealthy. He had accumulated much attention from the fashion press, thrown himself entirely into the job, done a lot of drugs, and John Galliano was almost bankrupt, since he had no business sense whatever. While his rapid early successes had made him the heir of Westwood, on the horizon were signs of self-destruction.

Such patterns continued into the 90s, when Galliano moved to Paris for his Autumn-Winter 1990-91 collection. Continuing rave reviews were accompanied by business failure: Galliano parted ways with a number of backers, and had to secure temporary support to complete his collections. His designs were simply too fantastical and technically complicated to sell en masse. Nevertheless, his talent, and talent for socialising, gained him some powerful friends: Vogue’s André Leon Talley, Anna Wintour and socialite São Schlumberger. The stage was set for a Hail Mary collection: The Black Show.35

Hosted at São Schlumberger’s 6th arrondissement Hotel Particulaire, the collection’s mise-en-scène, brought together by Amanda Harlech, comprised antiques, broken chandeliers, fallen candelabra, dead leaves and dry-ice. It had “a new way of seating people, so that it wasn’t on benches in the tent in the Louvre”36, bringing the audience into the theatre of the event, “so close they could smell the perfume of the girls.”37 The tight budget necessitated a single, off-the-shelf fabric: black satin-backed crepe. Galliano used “the wrong side and the right side [to] make the dresses look different… mix[ing] the shiny side and matte side, and so on.”38 The designs continued the story of his previous Princess Lucretia collection (S/S 1994)—a widowed Russian aristocrat seizing the day in Paris. Eighteen striking looks inspired by French Japonisme and 1930s Paris were modelled for free by the uber-famous Nadja Auermann, Carla Bruni, Christy Turlington, Shalom Harlow, Naomi Campbell, Kate Moss, Linda Evangelista, and others. It was a roaring success, and further success followed. A year later, having caught the attention of LVMH’s Bernard Arnault, he was announced as the Creative Director of the House of Givenchy. He was the only Englishman since Worth to head a French couture house: Galliano had made it to the big leagues.

John Galliano was certainly successful. To make a similar statement about Antonin Artaud is more difficult. Artaud has often been accused of having “created ‘an art without works’”.39 As Susan Sontag writes, “What he bequeathed was not achieved works of art but a singular presence, a poetics, an aesthetics of thought, a theology of culture, and a phenomenology of suffering.”40 It is true that Artaud’s vision of theatre, the Theatre of Cruelty, was never truly achieved. Even so, Artaud did stage a number of plays under his own, independent direction: those at Théâtre Alfred Jarry and his version of Shelley’s The Cenci.41 Artaud set up Théâtre Alfred Jarry, inspired by Ubu Roi’s controversial playwright, with two fellow former Surrealists, Roger Vitrac and Robert Aron. Aron produced and managed, Vitrac (mostly) “wrote the plays [and] Artaud directed and designed all the productions.”42 The troupe’s manifestos are prefigurations of the Theatre of Cruelty (a full elucidation thereof will come in the second essay of this series):

“The show we are watching must be unique and give us the impression of being as unexpected and as incapable of being repeated as any act in life…”43

“This is the human anxiety the audience must feel when they come out. They will be shaken and irritated by the inner dynamism of the production… this dynamism will be directly related to the anxiety and the pre-occupations of their entire lives.”44

“In a word, we ask our audiences to join with us, inwardly, deeply.”45

“theatre will no longer be a straight-jacketed thing, imprisoned in the restricted area of the stage, but will really aim at becoming action”.46

Seven productions were staged, including Strindberg’s A Dream Play, Claudel’s Act III of Le Partage de midi and a number of their own compositions. How successful was Théâtre Alfred Jarry? Some quick context: before the early twentieth century, directors were essentially just stage managers, with the playwright, actors and scene-designers significantly more important to the creative process. Powerful editorial directors, such as André Antoine, Lugné-Poe and later Charles Dullin, pioneered a transition to a more autocratic theatre—a director whose own ideas were paramount. This was essential to the development of avant-garde theatre, catalysing innovative visions of theatre, especially Artaud’s.

In this respect, Artaud had significant freedom in carrying out his proto-Theatre of Cruelty plans. TAJ was launched on 1st June 1927, and, having been widely publicised, was attended by much of Paris’ intellectual elite, including such greats as Paul Valéry and André Gide.47 Its limited run makes it difficult to view as a success, and, coupled with its funding and staging difficulties, one could consider TAJ’s promise unfulfilled. Indeed, Artaud himself was concerned that those who attended, seeking avant-garde theatre, were “prejudiced… of the I was there or flippant sort.”48 The audience, going into it with the expectation of being shocked, actually “found it quite normal.”49 It gained a reputation for superficial shock value, rather than the aesthetic transfiguration Artaud had hoped for.

Some scholars, however, do consider the TAJ period to have been a success, both in itself, and as a testing ground for Artaud’s theories. One major success, writes Kimberly Jannarone, was Artaud’s mise-en-scène. His play Ventre brûlé, ou la Mère folle (Burnt Stomach, or the Mad Mother) utilised a “piercing violet spotlight with a life of its own [that] acted as the assassin of each character”, while throughout played the “sounds of a persistent percussion and contrabass orchestra… a kind of marche funèbre, partly grotesque, partly poignant.”50 For Artaud, the playwright’s script was too often a performance’s gaoler; the play required freeing from this false reality. As he explained in a letter to Gide, the true reality of theatre had to be “liberated by means of spectacle, and therefore by mise-en-scène… that is,… the language of everything that can be put on the stage. Here, therefore, the director becomes the author, that is, the creator.”51 This ‘theatrical death of the author’ separates the actors and director from the playwright, and his script, and allows those who take part in the play just as much licence in interpretation as those who watch it.

We find in Théâtre Alfred Jarry, therefore, a mixed legacy. Unsuccessful in being avant-garde yet successful in presenting Artaud’s early ideas, the Théâtre Alfred Jarry was a prototype of the Theatre of Cruelty. Yet, more experimentation was needed. In 1935 came Les Cenci, the final attempt at putting his theory into practice before his institutionalisation in 1937.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

“If I am the chief of sinners, I am the chief of sufferers also.”—Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Robert Louis Stevenson.

“Fashion appears to have changed. It is now as much about theatre as about the clothes.” Marion Hume on Galliano’s first Givenchy show, Independent, 17 October 1996.

“I understand prohibiting the sale [of drugs] to addicts, but not to an unfortunate type like me who needs it so that he no longer suffers.”—Antonin Artaud.52

All good things must come to an end. A star shines only so long. Yet, before it collapses in on itself, it shines the brightest, in a shocking supernova. Galliano and Artaud lived life on the edge, constantly oscillating between disaster and success. For Galliano, after an Everest-like peak, always came a dramatic, alcohol-fuelled trough. For Artaud, failure in practical theatre was nevertheless accompanied by a poetry of theory.

We return to Galliano, now creative director at Givenchy. This period was brief, but triumphant. Two important aspects of his personality again rear their head. At Givenchy, he “took advantage of all the old-school protocol of directing rather than doing… no drawing, no cutting or pinning or sewing.”53 It was the overall aesthetic, and its theatre, that mattered most, and he was its dictator. The job also exacerbated his out-of-control addictions: “he would take anything he could find—anti-inflammatories, codeine—and mix it with alcohol. He did whatever he could to get a buzz.”54 At one point, he even went ‘AWOL’ two weeks before a collection’s release.55 Yet, according to Bernard Arnault, Galliano could do no wrong: “[he] walks on water… He is too good for Givenchy. I am putting him at Dior.”56

Galliano spent 14 years at Dior, so I cannot relate that era in its entirety. Instead, I shall provide two brief, and opposing, case studies of success and so-called failure: A Poetic Tribute to the Marchesa Casati (Dior S/S 1998) and A Voyage on the Diorient Express or Princess Pocahontas (Dior A/W 1998-99). Marchesa Casati, based on early twentieth century socialite Luisa Casati, was Galliano at his most fantastical. Staged at the Opéra Garnier in Paris, models in six acts and a prologue processed down the grand staircase, as if attending a masked ball. Characters straight out of Boldini portraits, wearing the most illustrious Edwardian gowns and Poiret-inspired dresses, stunned the audience, who felt like they themselves had been transported to one of the Marchesa’s famous balls. The show was a radical success. As The Times put it: “Galliano Glories in Pure Escapism.”57

In contrast, the next haute couture show Diorient Express was received poorly. Staged at Gare d’Austerlitz, the show began with a working steam train “burst[ing] through a panel of orange silk to reveal Princess Pocahontas seated at the front, flanked by two politically incorrect Native American “braves” to each side.”58 Galliano was creating alternate history—Pocahontas in Tudor England. A particular highlight was a “Henry VIII-style coat of white doeskin, embroidered and appliquéd with floral slips by Maison Muller, [that] used 180m of gold braid and took 2000 hours to complete.”59 Though technically astonishing, the collection was deemed by the press to be closer to costume than clothing. As The Times said: “Galliano goes off the rails in fashion fantasy.”60 Yves Saint-Laurent complained that Galliano’s shows were “ridiculous spectacle which would be better placed on a concert stage.”61

Throughout Galliano’s time at Dior, success was concomitant with excess. Galliano’s extravagant style as creative director aligned exactly with Bernard Arnault’s vision of haute couture. No longer just the domain of high society socialites, haute couture was transformed into a marketing scheme for the mass commercialisation of ready-to-wear and accessories. Galliano’s headline-attracting shows (assisted by Alexander McQueen’s at Givenchy) consistently brought new customers to Dior, with sales figures off the charts. Celebrities began wearing haute couture, and especially Dior, en masse, exemplified by Nicole Kidman’s famous ‘Chinoiserie chartreuse Dior dress’ she wore at the 69th Academy Awards. The inevitable consequence of this was pressure—heaps and heaps of it. And Galliano couldn’t handle it:

“After every creative high, I would crash and the drink would help me to escape… I started to have panic attacks and anxiety attacks, and I couldn’t go to work without taking Valium… sometimes I was taking sleeping pills during the day.”62

Compounded in 2007 by the death of Steven Robinson, his close friend and deputy at Dior and John Galliano, Galliano began to spiral out of control. In early 2011, everything collapsed around him. The Sun released a video of a drunk Galliano praising Hitler and harassing some Jewish women at his favourite bar La Perle. Their crime, being ‘ugly’—a sign of Galliano’s excessive aestheticising?63 Rapidly, he was suspended from Dior and John Galliano, and later convicted in a French court of making anti-semitic remarks and given suspended fines of €6,000. He claims not to remember the incident at all. The world reviled him. It was over.

“As long as [Artaud] kept his lucidity, he was fantastic. Royal. Prodigious in his vision. Funny in his repartees. He was completely lubricated with humour. But when, under the effect of drugs or illness, his escapades submerged him, the machine began to creak and it was painful, wretched. One suffered for him.”64

“Artaud is an example of a willed classic—an author whom the culture attempts to assimilate but who remains profoundly indigestible. [He] overpower[s] and exhaust[s] if ready in large quantities… For anyone who reads Artaud through, he remains fiercely out of reach, an unassimilable voice and presence.”—Susan Sontag.65

There are many myths of Artaud. Artaud is as much an idea—that which Mishima had obsessively sought for himself—as he is an historical figure. In the Anglophone and theatrical worlds, Artaud is usually the Artaud of the Theatre of Cruelty. In the Francophone and philosophical worlds, Artaud has been “presented in the company of Nietzsche and Bataille as one of the principal modern challengers to the ‘subject’ and to knowledges precipitated upon it.”66 Sontag documents both views, but wrongly assumes, on account of its incoherence, that “the character of Artaud’s writings forbids their being treated simply as “literature.””67 Following an expansive view of literature, in fact, allows all of Artaud to be treated as literature; or, rather, to do as Artaud did, and contemplate all sources of truth in a holistic and interdisciplinary manner. For Artaud engenders endless interpretation; all approaches to Artaud are by nature schizophrenic. We can only attempt to approach him; it is impossible to reach him, ever. The Artaudian corpus is expansive, yet fractal, and much is overlooked, such as his poetic works. Madness characterises it, just as madness characterised his life.

Much of Artaud’s corpus has a sort of ‘bipolar’ nature, dualistic in essence. We observe his conception of the ‘double’, his Gnosticism, and his obsession with the “antagonism between mind and matter, ideas and forms, abstract and concrete”, et cetera.68 The works themselves were deeply serious; yet, in many cases, also deeply humorous, and thus, at times, quite capricious. In his opinion, contemporary theatre had declined “because on the one hand it has lost any feeling for seriousness, and on the other laughter.”69 At “the basis of all poetry” was a “profoundly anarchic spirit”, with laughter having a “physical, anarchic dissolving power.”70 Poetry “questions all object relationships or those between meaning and form.”71 Thus with poetry comes “Danger.”72 Seriousness and humour—these dual anarchies—face danger head-on. Both bring truth. The inability of contemporary theatre to grapple with this fundamental truth required remedy—what became the Theatre of Cruelty.

Les Cenci, staged in 1935 and adapted from Shelley’s five-act The Cenci, was “not Theatre of Cruelty… but a preparation for it” (which Artaud claimed after its commercial failure).73 But it was Artaud’s last, real attempt at implementing his vision. Here is the plot, summarised:

“The story centres on Count Francesco Cenci, who is notorious for his depravity. He gives a party at which, to the horror of his guests, he gleefully announces the deaths of two of his sons. Another victim of his cruelty is his daughter Beatrice, whom he has raped. Beatrice enlists the help of Orsino, a priest and Roman nobleman whom she had once hoped to marry. With the approval of the Cenci family, Orsino plots the murder of the count. When the other conspirators are found out, Orsino evades capture; the rest are tried and executed.”74

Artaud’s Les Cenci is radically different to Shelley’s. He severely cuts dialogue, motivated by his hatred of words, and eliminates, according to Goodall, Shelley’s Shakespearean “psychological exegesis”: “he shifts the emphasis from diegetic to mimetic forms of representation… the focus is concentrated almost exclusively on what the audience is to witness.”75 Action and will are united into an unstoppable force. Rapid movements and chaotic rhythms become the landscape of the stage. In one instance, “[Beatrice’s] defiance of [Count Cenci] takes the form of an attempt to generate a rival force-field; she traces an orbit of her own, temporarily holding possession of the central arenas as she issues threats on behalf of her remaining brothers.”76 The actors’ movements are musically accompanied by “four loudspeakers at cardinal points in the auditorium”, emitting ‘acousmatic sound’, that is, “sound that has no visual referent… link[ed] to the mysterious powers and affectives force of Cenci, whose actions are meant to elicit the unconcious impulses… central to Artaud’s philosophy.”77 Artaud was pursuing the unconciousness of the Theatre of Cruelty.

So was Les Cenci successful? Commercially, it failed, with only 17 performances staged before its shut-down. Dramaturgically, the traditional view holds that it was unsuccessful, contributing to the standard view that Artaud created nothing but ‘an art without works.’ There was, certainly, much consternation from contemporary reviewers, who viewed it as “paroxysm from beginning to end”,78 wherein “our ears [were] tortured by deafening music”.79 More recently, attempts at rehabilitation have been made by scholars following Artaud’s own defence in La Bête noire: The “clash of contradictory and divided judgements”, echoed in an audience that was “laughing like lunatics, trembling with hysterical laughter,” was a sign that the Theatre of Cruelty was working as intended, since it had “pulverize[d], mesmeri[sed] the audience’s sensibilities.”80 Perhaps the audience found it so alien that they were incapable of putting the experience into words, which was Artaud’s whole point, after all!

While Les Cenci may no longer have a wholly negative legacy, it was nevertheless a major personal failure that caused Artaud to spiral irrevocably out of control. Unable to raise any money for further productions, he decided to travel the world, seeking ‘cultural secrets’ that might inspire him. Mexico in 1936, where he apparently studied Mesoamerican peyote rites, was followed by Ireland in 1937, where he sought out the Druids and became increasingly convinced of the oncoming apocalypse. Artaud explained his motivation: “Jesus-Christ… is giving me orders about everything that I am going to undertake.”81 He began to live in homeless shelters, fought with Dublin policemen and “caused a commotion at a Jesuit college”, upon which he was arrested, held at Mountjoy Prison and deported back to France. Claiming different, bizarre identities, including being a Greek ‘Antonéo Arlaud Arlanapulos’ and “a member of the French Royalist party, [fearing] being guillotined if returned to France”, he fought with two ship mechanics, whom he paranoiacally accused of wanting “to make him disappear”, was forced into a straitjacket, and sectioned.82

He remained until 1946 in various asylums, and was to some extent creatively rehabilitated at Rodez, the last of many. Having been diagnosed with cancer in early 1948, his drug-doses greatly increased, to cope with the pain. On the 4th March, the gardener of the clinic his friends had placed him in found him “seated at the foot of his bed, grasping a slipper, the empty bottle of chloral hydrate on the floor, nearby”—dead.83

Explicit

“I don’t come from this world,[…] I am not like the other men born of a father and a mother, [..] I remember the infinite sequence of my lives before my so-called birth in Marseille on 4 September 1896, at 4 rue du Jardin des Plantes, and [..] the other place from where I come is not the sky, but like the hell of the land in perpetuity. Five thousand years ago, I was in China with a cane history attributes to Lao-Tseu, but 2,000 years ago, I was in Judea…”—Antonin Artaud

“For me, it’s a fleeting moment.”—John Galliano on fashion.

It never is truly over. After Rodez, Artaud produced, some say, among his greatest works, including Van Gogh le suicidé de la société and Pour en Finir avec le Jugement de Dieu. The latter, which was not circulated until many years later due to its obscenity, may have been the closest thing to a fulfilment of the Theatre of Cruelty, though it was limited by its performance being on radio. Even now, the spectre of Artaud haunts theatre, and many other modes of expression. The idea of Artaud is far more concrete than he was ever capable of being, since he, “mythologized as an icon of failure and madness, has achieved the pathos of a martyrdom.”84 While he may have exclaimed, “I am a fanatic, I am not a madman”, he is nevertheless remembered for his generative, and degenerative, madness.

John Galliano is chiefly remembered for that self-destructive, hateful episode. In all scenarios, and most especially in success, that moment in time is always recalled— however sublime his achievements may have been. Galliano may not be as obviously mad as Artaud, but similar struggles with substance abuse and an uninhibited appetite for creation place them in the same intellectual, and poetic, cadre. But it is not over for John Galliano, now creative director at Maison Margiela. Genius is genius, and remains genius. His genius is on display—there is no better example than the 2024 Artisanal Collection.

Do genius and madness have a symbiotic relationship? Is it that madness creates genius, or the other way around? I cannot say. Certainly, both of these men were possessed by some sort of ecstatic energy, which pushed them on and on—what Artaud termed ‘cruelty’. The greatest tragedy comes not in their individual suffering, but in their creations being overshadowed by their individual madness. We must remember pioneers for their singular works, divinely inspired, not just for their flawed, but fascinating, psychologies.

N.B. Pluviôse was the French Republican calendar month from between the 20th and 22nd January and between the 18th and 20th February.

Italics are from Ezra Pound Canto I.

Cf. Antonin Artaud, The Theatre and Its Double (1938; tr. V. Corti, 2010), 36. (From now on TD)

TD, 59; TD, 66.

TD, 88.

Nietzsche, The Gay Science, tr. R. Kevin Hill, Section 111.

Thomas, D: Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano (2015), 24. (From now on G&K)

Mulvagh, J: Vivienne Westwood : an unfashionable life (2003), 139; https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/vivienne-westwood-punk-fashion-sex-pistols-cec/index.html.

G&K, 32; article on Taboo: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2013/jun/22/club-catwalk-london-fashion-1980s

G&K, 35.

https://www.indiewire.com/criticism/movies/high-and-low-john-galliano-review-1234901895/

G&K, 36.

Mulvagh, J: Vivienne Westwood : an unfashionable life (2003), 139.

Mulvagh, J: Vivienne Westwood : an unfashionable life (2003), 142.

G&K, 36.

G&K, 40.

de Meredieu, F: C’etait Antonin Artaud (2006), in: Shafer, D. A.: Antonin Artaud (2016), 19.

Morris, B. Antonin Artaud (2022), 3.

Morris, 3; referring to TD, 50.

Lotringer, S., Spinks, J.: Mad Like Artaud, 12 — attributes this to a reveal of being Jewish…

Morris, 5.

Shafer, 25.

Morris, 6.

Yeats, W.B. The Trembling of the Veil.

Artaud, A., Sontag, S. (ed.), Weaver, S. (tr.): Antonin Artaud: Selected Writings (1988), 17.

Morris, 9: quoting Tian 2018. Cf. Artaud, TD, 61.

Morris, 8.

Morris, 8, quoting Artaud, Collected Works Vol. II, 130.

Morris, 14.

Surrealist Manifesto.

Morris, 20, quoting Esslin 1976, p. 29.

G&K, 51.

Amanda Harlech, High and Low, 31:42.

Kerry Taylor, Galliano: Spectacular Fashion (2019), 98.

High and Low, 30:13.

Morris, 75.

Sontag, S. “Approaching Artaud”, Under the Sign of Saturn (1980), 17.

He also left vast works of poetry and other writings, which have not been of as much interest to scholars who care mainly about his theatrical / aesthetic theories.

Morris, 77 (from Melzer 1977, 133).

Collected Works 2, 18. (From on CW)

CW 2, 18.

CW 2, 18-19.

CW 2, 26.

Jannarone, K.: “Theatre before its double: Artaud directs in the Alfred Jarry Theatre” (2005).

Morris, 79, quoting Melzer 1966, 133 and Artaud Collected Works 2, p. 37.

Morris, 79, quoting Melzer 1966, 136.

Jannarone 2005, 252.

Sontag 1988, 299.

Shafer, 43.

G&K, 246.

G&K, 250.

Ibid.

G&K, 254.

Times headline 20 January 1998 (quoted in Spectacular Fashion).

Spectacular Fashion, 173.

Ibid.

Times 21 July 1998 (quoted in Spectacular Fashion).

G&K, 323.

G&K, 476.

G&K, 469. Note that I do not reproduce what he said out of fear of Substack guidelines!

Morris, 5, quoting Barrault, 1974, 81.

Sontag 1980, 70.

Goodall, J.: Artaud and the Gnostic Drama (1994), 2.

Sontag 1980, 67.

TD, 37

TD, 29.

Ibid.

TD, 30.

TD, 29.

Blin et al. 1973, quoting La Bete Noire No. 2 May 1 1935.

www.britannica.com/topic/The-Cenci

Goodall, J.: “Artaud’s Revision of Shelley’s “The Cenci”: The Text and its Double” (1987), 119.

Goodall 1987, 121.

Curtin, A.: “Cruel Vibrations: Sounding Out Antonin Artaud’s Production of Les Cenci” (2010), 251.

Curtin 2010, 254.

Curtin 2010, 255.

Curtin 2010 255; ibid.; TD, 63.

Morris, 33, quoting Artaud, 2019 (tr. Barber), 46.

Shafer, 152-3.

Shafer, 205.

Goodall 1994, 1.