Sans cesse à mes côtés s'agite le Démon;

II nage autour de moi comme un air impalpable;

Je l'avale et le sens qui brûle mon poumon

Et l'emplit d'un désir éternel et coupable.

The Demon is always moving about at my side;

He floats about me like an impalpable air;

I swallow him, I feel him burn my lungs

And fill them with an eternal, sinful desire.

Baudelaire, La Destruction (1-4; tr. Aggeler).

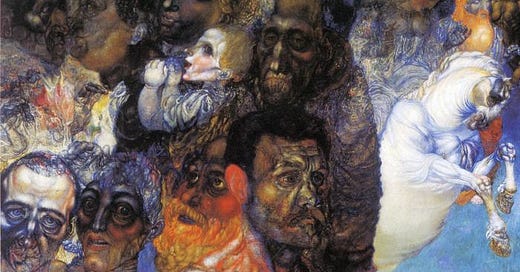

The spectators were stunned. Maison Margiela’s 2024 Artisanal Collection mesmerised them. Swaying in cadence, the grim ghosts of eternal Paris stole past, symbols of the universal archetypes, poetically truthful in all their untruth. Metaphysics had entered the mind of the audience. Gesture, rhythm, costume and crime had raised the human body to the dignity of signs. Antonin Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty was made manifest by the genius of John Galliano.

That mist, whence came the damaged dolls, encircles us all. It is a suffocating fog, chaotic and strange; yet life-giving and wonderful. This smog of irrationality chokes Reason; and it must choke Reason, when Reason smothers truth. Joyfully, when that mass of mist at last precipitates, beauty rains down in spades. Truth, like a brilliant rainbow roaring across the sky, makes itself clear. For now, however, our minds remain cloudy, they continue to confuse us—truly, what was it that compelled Galliano and Artaud? This mist must dissipate; these clouds must give way. In its place must come a glaring sun—of strict examination.

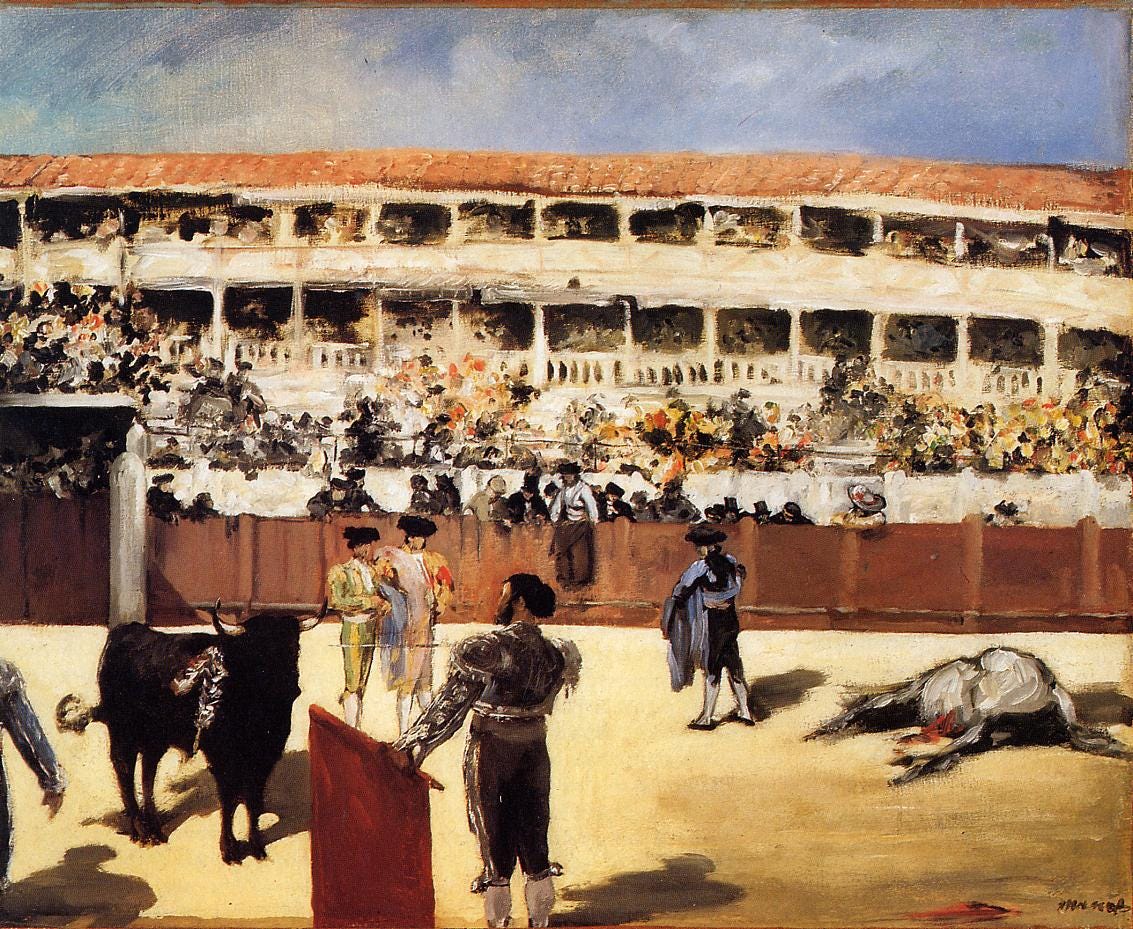

“One of the most beautiful, most curious and most terrible spectacles one can see is a bull hunt. On my return, I hope to put on canvas the brilliant, flickering and at the same time dramatic appearance of the corrida I attended.”

—Édouard Manet, Letter to Baudelaire, 14th September 1865.

Tercio de Varas

Parfois il prend, sachant mon grand amour de l'Art,

La forme de la plus séduisante des femmes,

Et, sous de spécieux prétextes de cafard,

Accoutume ma lèvre à des philtres infâmes.

Sometimes, knowing my deep love for Art, he assumes

The form of a most seductive woman,

And, with pretexts specious and hypocritical,

Accustoms my lips to infamous philtres.

Baudelaire, La Destruction (5-8; tr. Aggeler).

“The greatest of blessings come to us through madness, when it is sent as a gift of the gods.”—Socrates, Plato’s Phaedrus.1

“INSPIRATION CERTAINLY EXISTS.”—Antonin Artaud, The Nerve Scale.2

Under this blazing sun fights the matador. His life is composition and performance. A man against nature, his Chaoskampf is enacted in a biological theatre. Around him the audience is arrayed. A panoptic stare fixes upon him; yet he does not falter. He is singular. They are plural. Yet in their plurality, they quickly become one, as fast as the bull’s blood seeps into the sand. His singularity derives from cruelty. A cruelty that makes matter out of madness.

Is ‘cruelty’—“the sense of hungering after life, cosmic strictness, relentless necessity, in the Gnostic sense of a living vortex engulfing darkness, in the sense of the inescapably necessary pain without which life could not continue”3—the overriding principle of genius? A driving purpose that, even through the most terrible madness, fixates on the ideal? An incessant creative impulse so powerful that those who have it are intoxicated with an unhinged brilliance? A shocking genius that might, at any one time, impair the mental faculties for the benefit of the artist’s creative abilities?

I have shown so far the radical approaches of Antonin Artaud and John Galliano, and how the success of Maison Margiela’s 2024 Artisanal Collection was tied to the principles of the Theatre of Cruelty. Both men suffered in life, from debilitating addictions and from social stigma. Both nevertheless succeeded in fundamentally altering their artistic fields. Both had unique, fantastical, pseudo-religious aesthetic visions tantamount to miracle. Like the matador, each man fought his battles with a necessary cruelty. The blood of victory—an emblem of ‘cruelty’—was drawn in an amphitheatrical atmosphere of judgment and self-judgment. Both bled as much as the bull.

How should we understand ‘cruelty’? Artaud’s writings are notoriously hard to interpret. Does ‘cruelty’ at all resemble the divine madness (θεία μανία / theia mania) of Plato? Elsewhere I considered divine madness the ‘trace-like state of sublimity’ that elevates us to transcendence.4 Just like divine madness, ‘cruelty’ is a seemingly irrational motivation, that grants the one in that state the capacity to achieve an “inexorable goal, whatever the cost.”5 Plato himself, though perhaps most responsible for the historical development of philosophy as a rational science of dialectic, in fact stresses the legitimacy of mania, and thus the irrational, in seeking eudaimonia (the ultimate goal of philosophy, broadly translated as happiness). In the Phaedrus, he outlines his four types: prophecy, inspired by Apollo; mystic/initiatory madness, inspired by Dionysus; poetic madness, inspired by the Muses; and erotic madness inspired by Aphrodite and Eros.6

Frustratingly, there is not much more detail than this in any of Plato’s other works. In fact, since these four categories are essentially reflective of Plato’s religious milieu—that of Athens with its mystery cults and oracles—our understanding of divine madness is unfortunately reduced back to the basic concept. This concept, being irrational, is impossible to define exactly; perhaps, instead, we might identify in Plato’s types certain universals that apply to all minds-divine. All does teem with symbol, as says dear Plotinus, and so we shall attempt to know them, trying to locate in the mundanities of now the universalities of forever. From this basis, I shall attempt to understand divine madness through Artaud’s concept of ‘cruelty’, which I posit as Artaud’s interpretation of his own divine possession. To do so, I must dive head-first into his Gnostic vortex, that ‘unassimilable’, ever-engulfing cosmic horror against which he constantly fought and which, in the end, defeated him.

Gnosis

“A Mana am I of the great Life. Who has thrown me into the suffering of the worlds, who has transported me to the evil darkness? So long I endured and dwelt in the world, so long I dwelt among the works of my hands.”—The Ginza Rabba, Mandaean scripture.7

“Art is not the imitation of life but life is the imitation of a transcendent principle with which art can put us back into communication.”—Antonin Artaud, The Theatre and Its Double.8

Long identified in Artaud has been “an obsession with doubleness—of the self, of the body, of the world, and of God—underl[ying] the agonistic dynamic which governs his dramaturgy.”9 His ultimate goal, and the goal of the Theatre of Cruelty, was always that ‘double’, that is, “the real”, which is more real than life itself.10 In this way, Artaud’s aesthetic-religious-spiritual philosophy closely resembles the Gnostic tradition. For him, the material world was a prison, where “evil is the paramount rule, [and] whatever is good is an effort”.11

‘Gnosticism’ is almost as hard to define as Artaud’s works are to interpret. Finding its origin in the first century AD, what we might call the ‘Gnostic tradition’ comprises a mangled mess of Christianity, Judaism, Neoplatonism, and other diverse religious movements. For our purposes, at least, Artaud’s reception is most relevant; the complicated internal distinctions of ‘Gnosticism’ fall away. His ‘Gnosticism’ is both broad and suitably chaotic. Explicit references, as we find in his definition of ‘cruelty’ are rare, but a consistent language nevertheless emerges from any reading of his Collected Works. Since a detailed elucidation of the characteristics of ‘Gnosticism’ would transform this essay into a never-ending tractate, I shall relate instead the fundamental elements of its system: the cosmogony; the nature of man; its dualism; and its non-traditional mythology.

The Gnostics believed in an unknowable, invisible, uncreated, transcendent God called the Monad, the One, or the Absolute, among other names.12 Being totally perfect and whole, he created nothing in the universe; rather, from him emanated divine light in the form of ‘aeons.’13 In a great cosmic catastrophe, one flawed ‘aeon’ Sophia (Σοφία - wisdom) foolishly attempted to emanate herself. This ‘flawed’ ‘aeon’, who, unlike the rest, had ‘passion’ or committed a ‘sin’, fell from the heavenly realm known as the Pleroma (πλήρωμα - divine fullness) and, in her terror at being separated from the Monad, accidentally created matter, soul, and, worst of all, the ‘Demiurge’, also named ‘Yaldabaoth’.14 The Demiurge created the material universe, but, being ignorant of the circumstances of his birth, was undermined by his mother Sophia, who inserted the divine spark into his creations, such as the first man, Adam.

This cosmogony leads to two conclusions. First, man has within him the ‘pneuma’ (divine spark), beyond even the soul and body, that desires to return to the Monad, but is kept in a state of ignorance by the Demiurge. The material universe is man’s prison, within which his divine spark is “unconscious of itself, benumbed, asleep, or intoxicated by the poison of the world.”15 The goal of Gnosticism, then, is knowledge of God, ‘gnosis’, a “reminder of man’s divine origin,” revealing the ‘pneuma’s’ “way out of the world, comprising the sacramental and magical preparations for its future ascent.”16 Second, the ‘Gnostic’ universe is dualistic, setting an ‘evil’ material world against the light of the ‘Good’, of the ‘Monad.’ The creation of the world, rather than being an act of divine benevolence, effected our ongoing separation from God.

Within this moral framework, the traditional mythology of Christianity and Judaism becomes deeply troubling, which can only be explained through an inversion of its symbolism. The Garden of Eden becomes a counterfeit paradise fabricated by the Demiurge, “where delight is deceit.”17 The serpent, sent by Sophia, coaxes Adam and Eve into eating the forbidden fruit, after which “they knew the power from beyond and turned away from [the Demiurge].”18 Instead of ‘original sin’, the eating of the apple “marks the beginning of all gnosis on earth.”19 Christ, however, retains all his cosmic significance, being, according to some, the Monad incarnate, send in order to enlighten the world, for which the Demiurge crucified him—“Through Him He enlightened those who were in darkness.”20

Artaud’s Gnosis

“When the hidden god creates, he obeys a cruel need for creation imposed on him, yet he cannot avoid creating, thus permitting an ever more condensed, ever more consumed nucleus of evil to enter the eye of the intentional vortex of good.”—Antonin Artaud, The Theatre and Its Double.21

“No imagery satisfies me unless it is also Knowledge, unless it bears its own substance as well as its own clarity.”—Antonin Artaud, The Theatre and Its Double.22

All his life, Artaud lived with an extreme awareness of the Gnostic ‘cosmic drama.’ Reality was an asylum, and he was its most rebellious inmate. Artaud believed that his mission was “to reveal this to all and it is a mystery as formidable and terrifying as that which claims christ to be the Prince of Destruction, come to be the aid of those who could see the evil of Life.”23 The ‘hidden god’, that is, the Demiurge, incessantly creates, injecting evil more and more into good. Artaud desired to teach, as the Gnostic figure of Christ did, “the secret detachment from the world, of return to the vanishing point of Life.”24 The ‘pneuma’ had to escape the world of matter.

In the arena of life, Artaud was under constant attack, both physical and mental. Trapped in a hostile mind, whose ideas would “abandon him… [crumble] beneath him or [leak] away”, and trapped in a hostile material universe, in which his body was the enemy, Artaud desired gnosis—liberation from the Demiurge’s creation.25 His writings, which he often characterised as mere ‘emissions’, are intensely vulgar, particularly about the body which is “sale carne galeuse, bondée de rats et de vieux pets” (filthy scabby meat, packed with rats and old farts) and “la viandasse de carne grayasse” (gross meat of gross-grey meat).26

Artaud wanted out. He considered suicide, but rejected it, needing first “to be given some real assurance of being”.27 Instead, it seems, likely through the works of the esotericist Éliphas Lévi, popular among the Surrealists and read by Rimbaud and Jarry, too, that Artaud discovered Gnosticism, or some semblance of it.28 He found his solace in Gnosticism’s ‘Basilidean’ strand, a theory of creation that posits a seed of divine self-reflection from which the Cosmos emerged, called the point suprême (another obsession of the Surrealists).29 As Artaud himself wrote in 1944:

“There is a point in the infinite upon which God thought, and which he touched as upon a preoccupation, an accusation, a designation of being: that was the origin of creation. It is when God sees himself as a self that things are stirred into becoming; before that he does not see himself, he thinks of the infinite.”30

The point suprême is a “catastrophic point of closure upon the multiplying emanations of the transcendent God, reopening on to the proliferating forms of demiurgical creation.”31 Thus, as the origin point of demiurgal creation, “movement in reverse would thus be the regression of demiurgical creation towards its point of annihilation.”32 In seeking this annihiliation, Artaud embarked upon a ‘counter-demiurgical project’—‘cruelty’—with the point suprême being “an extreme point of depletion reached through prolonged physical ordeal”:33

“I was … at the extreme point of suffering where there is nothing, beyond any rallying thought. [In] a kind of mutable and slippery despair, rent by conflicting impulsions, [on] a sort of crazed flightpath across the soul where, from the exterior to the interior, I sensed the constant reabsorption and dying away of my thought. Form cancelled itself in explosive flashes.”34

‘Cruelty’ is that “sense of hungering after life, cosmic strictness, relentless necessity, in the Gnostic sense of a living vortex engulfing darkness, in the sense of the inescapably necessary pain without which life could not continue.”35 ‘Cruelty’ is gnosis. ‘Cruelty’, and the praecepts of the Theatre of Cruelty, will construct an ‘intelligent body’ in order to transcend mind and body, both tormented in Artaud’s case. As he writes, “there is a mind in the flesh, a mind quick as lightning.”36 Theatre, having a “physical aspect” is best suited for the ‘intelligent body’ to make ‘metaphysics enter the mind’, and thus launch the total cultural revolution which Artaud had always desired, and which Surrealism failed to achieve.

In this way, the ‘pneuma’, the divine spark, trapped by the demiurgical universe, will be freed, through a strict fixation on the divine. Artaud’s madness, in that sense, comprises his radical rejection of the material universe, in favour of a passionate striving towards transcendence, ‘at any cost’. Accordingly, the Dionysian and the Apollonian, necessarily being impulses predicated on the boundaries and antagonisms of order and chaos, fall away. Indeed, all things fall away, returning to that ‘vanishing point’, the point suprême. Total annihilation and union with God (but not the demiurgical God of this world) become one and the same.

Theosis

‘Cruelty’ as intense fixation has certain similarities with esoteric religious practices. Eastern Orthodoxy has hesychasm, that is, an intense contemplation of the divine in the form of the Jesus prayer, rhythmically repeated: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy upon me, a sinner.” The ultimate aim of this practice is theosis, “deification”, in the sense of ‘union with God.’ He who aims for theosis must achieve hesychia, “inner stillness and creative silence”, nepsis, “sobriety, vigilance, spiritual insight”—both bringing catharsis—and finally theoria, “illumination” or “contemplative vision”. This theoria, ironic in etymology, is actually the highest form of praxis, being direct experience (peira) of God.37 Thus we understand a Christian definition of gnosis, which takes place internally, deep within the individual Christian’s heart.

Islam finds itself with a similar practice, dhikr, “remembrance [of God]”, wherein the one praying repeats such phrases as inshallah, “God willing”, Bismillah, “in the name of God”, etc.38 In the Sufi interpretation, dhikr is “the polish for the heart”, with the aim of making the heart “the locus for the direct manifestations of God’s Names and Qualities” (which are often the phrases repeated in dhikr).39 Dhikr thus allows the dhakir, “the one remembering”, knowledge of God, and, most important in Islam, knowledge of his tawhid, “Oneness”.40 It returns man back to the primordial state (al-fitrah), when “the heart was directly accessible… [living] with God and in God.”41 Sufi poetry sings of an intense fixation on God, often couched in the language of the lover, with God as the poet’s ‘beloved’, and love as means of knowing God. Hence Rumi: “That is Love, to fly heavenward, / To tear a hundred veils at every moment…”42 Love and prayer form a sort of doublet—both gifts from God that permit us to know him transcendentally. Is divine madness, then, closer knowledge of God?

The location of this contemplation occurs at the point vierge, a Christian parallel of the point suprême. This is the “deep heart” of the Psalms and the “last, irreducible, secret centre of the heart” of Sufi mystic al-Hallaj, being ““where God alone has access and human and divine meet”; it embodies the “sacredness hidden at the depth of every human soul”.”43 This point vierge is the setting of hesychasm and dhikr, where the boundary between God and man is thinnest—“pre-eminently the place of Divine immanence, the locus of God’s indwelling.”44 Indeed, in Islam the heart (qalb) is identified “esoterically” with “the Ka’bah, where the All-Merciful (ar-Rahman) resides.”45 The goal becomes “to develop a heart that knows God.”46 Hence again Rumi: “I have looked into my own heart; it is there that I have seen Him; He was nowhere else.”47

Artaud’s ‘cruelty’ demonstrates a will to transcendence concomitant with annihilation. Artaud’s intense religiosity, Greek upbringing, and “double movement of fascination and profound mistrust… [of] a wide range of esoteric literatures” served as obvious influences. Indeed, his breathing exercises, stemming from his time at Charles Dullin’s troupe, resemble the breathing exercises of Christian and Islamic mysticism. His divine madness was a driven madness, fixating upon a single goal: gnosis.

Tercio de Banderillas

II me conduit ainsi, loin du regard de Dieu,

Haletant et brisé de fatigue, au milieu

Des plaines de l'Ennui, profondes et désertes,

He leads me thus, far from the sight of God,

Panting and broken with fatigue, into the midst

Of the plains of Ennui, endless and deserted,

Baudelaire, La Destruction (9-11; tr. Aggeler).

In the coursing of the bulls, the matador is centre stage. He is a vicious protagonist, crueller than cruel, in constant battle with nature—for nature is crueller than he. Glistening, the beast’s keratin spikes taunt the toreador, craving the crust of his itching skin. Like shafts, they long to make a sheath in the substance of his flesh. Rippling tendons, dark with heat, tear towards him—a bull-god as ancient as the Guisando verracos.

The matador, like Galliano, like Artaud, is an addict. Yet his ultimate addiction is not to dopamine, or to any other inflammation of reality, but to the act of creation—union with the ideal. The hecatombs on hecatombs of eviscerated carcasses are merely fodder—fodder for the creative mind.

The matador is hero and anti-hero, a duality in creativity. His genius comes in his distinction. Distinct from all others, even his cuadrilla, whom he commands as caballero, he makes a distinct work, of distinct elements, of distinct character. In his cruelty we identify Knight, Death and the Devil.

The cruelty of genius is counterintuitively ascetic in nature. Yet rather than becoming a stylite, an anchorite, or even a dendrite, and thus shielding himself from the oncoming storm, the man of cruelty allows himself to be carried along with it, drawn into the ‘living vortex.’ Amidst the madness, stands a man among the ruins—of his sanity, his physical body, his innocence—and yet, anew, he erects sparkling monuments with utopian proportions. Stimulated by a sublime terror, the mad genius focusses intensely on a single purpose, at the expense of all other things.

However, while alone, the matador’s victory is an impossibility—he requires his crew. His performance requires a dramatis personae, comprising the banderilleros (flagmen), picadores (lancers), the mozo de espada (sword servant), the ayuda (aide), subalternos (subalterns) and peones (assistants). These men manage the corrida with its innumerable interchanging, interweaving, interlocking elements. The matador issues the commands that place them into order.

Dictator-Creator

“I announce to you the coming of a dictator: Antonin Artaud is the one who has cast himself upon the sea. Today he is assuming the task of leading forty volunteers towards an unknown abyss, where there burns a great torch that will spare nothing, not your schools, not your lives, not your most secret thoughts.”— Louis Aragon, La Revolution Surrealiste.48

Artaud’s divine madness was ‘cruelty.’ This ‘cruelty’, in pursuit of divine annihilation, like the theosis of Christian or Islamic mysticism, entailed a strict, vicious fixation on creation and, in the case of theatre, a metaphysical revolution. Such an intense fixation meant an abandonment of mundane cares and concerns. The toxicity of modernity could not allow truly monk-like conditions to thrive; rather, a constant battle against the Demiurge’s forces—the terrors and wounding horns of reality—had to be waged. Galliano and Artaud, matadors, were gored by the bull.

Each man, simultaneously a dictator and a creator, held firm to one focus, all throughout his life, with all its vicissitudes. In theatre and in fashion, both men held to this tenet of the Theatre of Cruelty:

“The old duality between author and producer will disappear, to be replaced by a kind of single Creator using and handling this language, responsible both for the play and the action.”49

The ritual of creation was all encompassing. Each created his own Gesamtkunstwerk as Artaud had described of the ‘producer’ of Balinese theatre: “a kind of organizer of magic, a master of holy ceremonies.”50 Artaud was, in producing and directing his form of theatre, poet, priest, dictator and creator. Sacralising profanity, he endeavoured to unleash a primal, sacred horror, which required his own metamorphosis into a “kind of demiurge.”51 As Georges Bataille wrote about meeting him: “I understood what he was saying, he had resolved to personify the state of mind of Thyestes when he realized he had devoured his own children.”52

This dictatorial instinct echoed the coming of the avant-garde, with its powerful editorial directors like André Antoine, Lugné-Poe and Charles Dullin. The ‘new theatre’ liberated the director’s vision, generating radical dramaturgical innovations. Though Artaud’s theatrical record was controversial, we have seen so far in this series that it was not necessarily a disaster, but perhaps misunderstood. The radicalism of Artaud’s vision could never satisfy those who were too firmly attached to their theatrical prejudices, whether too tolerant of the avant-garde, or not tolerant enough. At Théâtre Alfred Jarry, Artaud freed theatre from the script and its author. With Les Cenci, Artaud broke the shackles of the Mind and set the audience into a state of “laughing like lunatics, trembling with hysterical laughter.”53 His unfettered vision placed him in the vanguard of the metaphysical revolution.

John Galliano’s own vision was that of a seer. His mantic fervour blazed, and continues to blaze, a trail in the world of fashion. Whether in the early days of Les Incroyables, or the highs of Dior, or now at Maison Margiela, Galliano’s chief asset was his imagination, which he was so skilfully able to make reality. His drive towards the ideal, which he found in his creative imagination, drew countless crowds and recruited fervent followers. With this almost magical power, Galliano directed each and every performance. As noted previously, he “took advantage of all the old-school protocol of directing rather than doing… no drawing, no cutting or pinning or sewing.”54 According to St Martin’s course director Bobby Hillson, “Galliano had this talent of getting people to do things for him. He had the capacity to inspire.”55 Nothing better evinced this than the turnout of the 90s supermodels, all working for free, at The Black Show.

The atelier hands, businessmen, models and customers put their total trust in him, permitting the couturier to take the creative risk that birthed A Poetic Tribute to the Marchesa Casati (Dior S/S 1998), among other triumphs. His ideas were like prophecies, and, as Amanda Harlech observed, “when John has an idea for a collection it’s called The Word… It’s then passed around to his whole team, each member adding and giving. It was always the most extraordinary experience.”56 He always had “a vivid sense of what he want[ed] to project, and he has made the spectacle his territory. For him, no fantasy is impossible.”57 Above all, Galliano was a ‘creator of images’, to which end he would grasp all opportunities and possibilities with zealotry.

Though perhaps not as hands-on as other designers, e.g. Alexander McQueen, in vision, Galliano was a dictator-creator. Brian Eno’s concept of the ‘scenius’, meaning “the intelligence of a whole operation or group of people”, partially applies.58 Galliano’s talent was in directing that operation, like a director directs a play; yet, he always remained its absolute leader, that is, a visionary, unafraid to pierce through the many layers of disruption that characterise life. The 2024 Artisanal Collection, though featuring the individual geniuses of Pat McGrath, Pat Boguslawksi, Duffy, Christian Louboutin, Leon Dame, Gwendoline Christie, Jordan Barrett, and others, could not have been begotten except by Galliano, for Galliano was the only one capable of bringing them all together, uniting that coterie in his singular genius.

Mythos

“Quelle extravagance! Quel succès fou!”—Women’s Wear Daily on Maasai (S/S 1997).

“Divine madness. Surely Galliano’s sixteen-year career has been a dress rehearsal for this sublime moment.”—Suzy Menkes on Maasai (S/S 1997)59

“إِنَّهُمْ كَانُوٓا۟ إِذَا قِيلَ لَهُمْ لَآ إِلَـٰهَ إِلَّا ٱللَّهُ يَسْتَكْبِرُونَ

وَيَقُولُونَ أَئِنَّا لَتَارِكُوٓا۟ ءَالِهَتِنَا لِشَاعِرٍۢ مَّجْنُونٍۭ

For whenever it was said to them ˹in the world˺, “There is no god ˹worthy of worship˺ except Allah,” they acted arrogantly

and argued, “Should we really abandon our gods for a mad poet?”

—Qur’an 37:35-6.60

Like the Gnostic, both Artaud and Galliano had a “seemingly reckless mythopoeic licence.”61 Both could pull together seemingly unrelated strands of thought or theme in order to create a masterpiece. Both could make The Word, kaleidoscopic and crystalline, flesh. Both made matter out of madness.

Artaud’s writings and productions were fundamentally chaotic and abstruse. Yet this absence of clarity did not entail an absence of meaning. Artaud’s works were in technicolour—he drew this myth, that religious tenet, this aesthetic principle and that philosophy all into his thought-world, melded and mixed them and sculpted out of that mix the statuary of a new literature. No influence was sacred or untouchable. All meaning would be distilled into him.

There was his Catholicism—hated and loved—East Asian theatre—Yuan-era Zaju, Japanese Nō and Balinese plays—alchemy, Kabbalah, the Egyptian Book of the Dead, the Tibetan Bardo Thodol, the Gnostic Apocalypse of John, among other uncountable esotericisms. In a carnivalesque spirit, Artaud delved the depths of mankind’s soul. Antonin Artaud was more of a surrealist than the Surrealists!

Galliano’s innovation was just as variegated. A voracious reader and a keen traveller, Galliano, with (until his death) Steven Robinson always at his side, would venture forth from the salons of Paris and dive deep into new worlds, real or imagined. For every collection, Galliano maintains ‘inspiration boards’, brimming with photographs, drawings, cloths, fabrics and colours. What seemed like creative frenzy soon becomes a creative framework: “believe me, you cannot find a logic. There is no logic. But then, he creates from that a total vision.”62

His first haute couture collection at Dior, Maasai (S/S 1997) provides a suitable example. Galliano, in such a fervour, dug through old newspapers, press releases, Dior’s 1947 Livres de Fabrications of Christian Dior’s first collection and Les Signes de Reconnaissance de la Maison Christian Dior—“a voluminous diary-like tome put together by the house that serves as an owner’s manual of sorts.”63 He took inspiration from leopardskin-wearing muse of Christian Dior Germaine ‘Mitzah’ Bricard, paintings by Giovanni Boldini and, uniquely, the Maasai people of Kenya and Tanzania. In a lightning strike of divine madness, Galliano, examining photos of the tribe, shrieked: “Oh my god! La Belle Epoque — the silhouettes are the same!”64

Over the years Galliano’s audiences would see collections influenced by Freud, ‘Trailer-Park Chic’, comic strips, dance, Marlene Dietrich, ancient Egypt, Empress Sissi, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Madame Butterfly and endless more.65 The flamboyance came from a belief in construction—in meaning! “After deconstruction, the only way to move forward and be modern was with construction, [but] with a lightness of touch. Not heavy or constipated.” 66 For some, however, the wild, radical aesthetic of Galliano was “too much. How can you be so creative all the time and stay sane?”67

Tercio de Muerte

Et jette dans mes yeux pleins de confusion

Des vêtements souillés, des blessures ouvertes,

Et l'appareil sanglant de la Destruction!

And thrusts before my eyes full of bewilderment,

Dirty filthy garments and open, gaping wounds,

And all the bloody instruments of Destruction!

Baudelaire, La Destruction (12-14; tr. Aggeler).

The picadores have done their duty—pierced the side of the bull. The banderilleros have fixed their barb-flags in its mountainous shoulders. Crippled, the bull struggles on, exhausted, bleeding, exhaling life. Now comes, at last, the dictator-creator, the mythical man, the matador—alone. In one hand, he grips the red muleta; in the other, the estoque, as sharp as a needle.

Now far from the madding crowd, the matador begins his faena. Turning, spinning, sliding, he snatches life from Death’s hands during each tanda. As the acrobat tosses himself in this and that direction, so the matador swerves from danger, contorting his intelligent body. Each tanda brings a dance as nimble and rhythmic as the flamenco.

In cold judgment sits the audience, awaiting the remate, the final flourish of the tanda. How can they possibly judge this man, who dares where others cower, craven? That is their hubris! They feign concern for safety, or cruelty—they call him mad! But who is madder, more perverted, than the voyeur?

Dipsas

In the Amores of Ovid, the elegies of Propertius and Roman drama exists the stock character of the lena. She is the bawd, the procuress, or the madam. She is the puella’s former wet-nurse, now enviously trying to take control of her charge’s sex life. To the elegiac lover, she is a witch and a sorceress, depriving him of his girl with curses and spells. The babushka at her very worst, the lena overreaches—no longer regulating society out of moral responsibility, but for the benefit of her own control. Dipsas, the bane of Ovid’s amatory existence, conjures the Magi’s tricks and Circe’s songs, spinning the bullroarer for Cybele, the Great Mother.

The lena’s modern equivalent is the New York Times journalist. Galliano’s mythopoeic power, so gloriously inspired, cannot possibly be permitted. No good deed goes unpunished. His experimentation, truly boundary-breaking, melds cultures together and glorifies them. But for Vanessa Friedman, NYT Fashion Editor, misery must trump creative ecstasy. In the lena’s world, Galliano’s collections tend towards insensitivity, cultural appropriation and parody: not “everything is fodder for the creative mind.”68

Dior Haute Couture Les Clochards or Homeless (S/S 2000), above all, risked the lena’s wrath. Galliano might be a genius, but for the ostracising schoolmarm, desperate for control, that genius must always be qualified. In every success, the whole world must be reminded of that self-destructive, hateful episode at La Perle, as if Galliano’s complicated, and often flawed, nature could be distilled into one mad instance. No, the crime which John Galliano was truly guilty of—that rant being just an excuse—was that he dared to subject everybody else to his genius, whether they liked it or not.

In the Artisanal Collection, he proved his mettle, “slicing [himself] open and letting the whole world see, warts and all, what [he was] about, what [he was] thinking.”69 The collection was the culmination of Galliano’s life efforts, bringing with him all his baggage, good and bad, with all those ebullient collections—Les Incroyables, The Black Show, Les Clochards, and more and more and more. In all that flamboyance and escapism—his totalising aesthetics—dwelt all along a passionate sincerity.

For Artaud, the lena was the asylum, with its lab-coats, goggles and quarantines. The lenae were men, doctors, experimenting with his sanity. Deported from Ireland for his maddening apocalypticisms, he was quickly stuffed into asylum after asylum. Most doctors declared him incurable. At Sainte-Anne, Jacques Lacan was convinced that Artaud’s “hopeless mental state [would] no doubt prohibit him from any creation” ever again.70 At Ville-Évrard, he received no treatment at all, but nevertheless began again to write to his friends and family. At Rodez, Gaston Ferdière became convinced that he could be cured—through electroshock therapy.

In the last section of his life, having been released from Rodez in 1946—fifty-two electroconvulsive treatments later—Artaud re-embarked on his cruel pursuit of a bodily and spiritual liberation. Though he denied that Ferdière’s treatment had ever helped him, he nevertheless had a new lease on life. Rapidly would come some of this greatest works, Van Gogh le suicidé de la société and Pour en Finir avec le Jugement de Dieu. Closer and closer he crept towards the Théâtre de la Cruauté, until death denied him that blood-soaked objective.

Antonin Artaud, le suicidé de la société

Odi profanum vulgus et arceo!

favete linguis: carmina non prius

audita Musarum sacerdos

virginibus puerisque canto.

I shun the uninitiated crowd and keep it at a distance!

Pray silence! As a priest of the Muses

I am singing to girls and boys

songs never heard before.

Horace, Odes (3.1.1-4; tr. Rudd).

Were either of these men truly mad? ‘Cruelty’, that “inescapably necessary pain without which life could not continue”, prioritises the driven act of creation over mundane affairs.71 Unburdened by the lena, by society, the man of cruelty has the required egoism to see everything as fodder for his creative mind. His unconventional genius—temporarily ordered madness—is tantamount to divine possession, and makes him unafraid of the misers and the schoolmarms.

He is a man of action, like the matador, who simultaneously alienates and attracts the voyeurs that make up his audience. They hate him and they love him. The tall poppy must be cut down, just like poor Euryalus—the sword, which fury guides, Driv'n with full force, had pierc'd his tender sides.72

Compare Artaud and Galliano. Are they all that different? Both were addicts. Both were obsessives, in constant combat with the world, and yet like ascetics. Was it merely Artaud’s oeuvre that made him seem mad? Vulgarity, profanity, sexuality, seeping from his mad head—was it so taboo as to make him insane in the hindsight of intellectual opinion? Wasn’t Artaud, as ‘unassimilable’ as he is to us, “always extremely conscious, intentional and wilful”?73 Is madness, then, socially defined?

Michel Foucault, in his famous Madness and Civilisation, “argues that the alleged scientific neutrality of modern medical treatments of insanity are in fact covers for controlling challenges to conventional bourgeois morality.”74 Above all, Artaud, along with Nietzsche and Van Gogh, challenged conventional psychiatry—the “lightning flash of [their] works… forever irreducible to those alienations that can be cured, resisting by their own strength that gigantic moral imprisonment which we are in the habit of calling, doubtless by antiphrasis, the liberation of the insane by Pinel and Tuke.”75

Artaud, of course, preceded Foucault in this sentiment. The Second Manifesto of the Theatre of Cruelty declares: “Repudiating psychological man with his clear-cut personality and feelings, it will appeal to the whole man, not social man submissive to the law, warped by religions and precepts”76 Was Artaud, then, not mad at all? Merely suffocated by the doctors at the asylum or the lenae that regulate society?

It seems that Galliano’s works were not mad enough, even if his personal life was perhaps as tumultuous as Artaud’s. Frequently drunk, Galliano would often throw his clothes off, dancing and prancing stark naked for all the world to see. On one occasion, he stood naked in a French hotel lift, for hours roaring at guests like a lion. He himself admitted that at one point: “I could have a conversation with a water pipe. I understand what that water pipe was saying… I just wanted to sleep forever.”77

Artaud remains trapped within the word, just as he was trapped within the world. The idea of Artaud, Sontag’s “singular presence, a poetics, an aesthetics of thought, a theology of culture, and a phenomenology of suffering”, haunts any sober analysis of his insanity. All things of Artaud are inextricably connected, impossible to divide, define or identify.

Successful madmen become prophets. This was Galliano’s fate, even after he destroyed himself. Both men could scarcely live with themselves; certainly both were medically unwell and required treatment. Yet it seems that the coherence of Galliano’s works, in contrast to the schizophrenic nature of Artaud’s, has permitted him to avoid diagnosis. As Christ is human and divine, the man of cruelty is sane and insane. If to create is to imitate God, the man of cruelty, pursuing the cosmic strictness of his radical goal, advances into the sublime realm overflowing with unreason.

For some, Artaud’s performances were “the unbearable exhibition of a mental patient.”78 For others, they were “the unprecedented attempt at exploding the boundaries of the theatrical event.”79 Galliano, at John Galliano, Givenchy, Dior and with the Maison Margiela 2024 Artisanal Collection, brought theatre into life. Poetry burst onto the runway, bringing with it the ‘double’—‘an expression of reality in irreality.’ Galliano has clung onto his sanity. Artaud, however, said Bataille, was “beyond the categories of reason and madness” altogether.80

Estocada; or, the vanishing point

—and now for the final tanda. With each flourish, the matador comes closer to the edge. Madness, and cruelty, urges him on, to risk his body for beauty. The bull, an animate effigy of nature itself, at all times strives to kill, to break, to crush him for his insolence. Yet he soldiers on, fixed on that single goal in mind—the estocada, the killing blow.

¡OLÉ!

It is Monday 13th January 1947. At Théâtre du Vieux-Colombier Antonin Artaud shivers and quakes in front of an overflowing audience of French intellectuals: Blin, Paulhan, Adamov, Gide, Breton, Camus, Braque, Picasso, Derain, Michaud, Audiberti and on and on and on.81 This crowd comes with sympathy; they hope the madman’s promise might at last be fulfilled. The vespers bring no answer but unease.

A man in the back row began to laugh and mock. Artaud—“The person who wants to make fun of me can wait for me outside. His place is not here.”

Artaud the Mômo has returned from exile—no more straitjackets! First the three poems: Le retour d’Artaud le mômo, Centre-mère et patron-minet and La culture indienne. Next the life-story—Smyrna, Marseille, Paris, Mexico, Ireland, Rodez, Ivry-sur-Seine… Then quick terrors: voice violent, begging, shouting, obliterating, a witch doctor cursing, bursting erupting emotion—electric shocks.

His notes littered all over the deck—he panics; three hours of glorious torture ended by André Gide shepherding him offstage.

¡OLÉ!

It is Thursday 25th January 2024. At Pont Alexandre III John Galliano unleashes his hellspawn upon Paris. His freakish models slink through subterranean sewers, occupy past and present. The audience fills the mise-en-scène; the grotesque pulverises the audience. The characters are typified to the limit; the human body is raised to the dignity of signs. The Theatre of Cruelty—Artaud’s mantic vision—groans to life, in bloody death.

John Galliano is far from finished.

¡OLÉ!

The matador, as exhausted as the bull, slips past the monster’s horns one last time. Now for the point. The game is nearly up. Curtain call. Muerte. Still.

He drives the tip into the vanishing point—where God and man are one.

As the estoque perforates the heart, the bull surges forward. The cheering crowd bays for blood. Quel succès fou…

He collapses. The beast heaves its mass as the two form a combined carcass. Gasps.

The mad toreador—impaled by his own hubris—still fixed on his goal—lunges for the trophy—slashes the right, then the left ear—as his arms give way—and fall to the sandy floor…

…

…

…

«¿Está enfermo alguno entre vosotros?

Llame a los presbíteros de la Iglesia,

que oren sobre él y le unjan

con óleo

en el nombre

del Señor…»

“The lower part a beast, a man above

The monument of their polluted love.”

—Aeneid VI.25-6 (Dryden).

Phaedrus, 244a.

CWI, 72.

Theatre and its Double (Second Letter to Jean Paulhan), 73.

Theatre and its Double (Letter to Mr R. de R.), 74.

Phaedrus, 265b.

G457f., in: Jonas 1958, The Gnostic Religion, 56. Jonas is potentially slightly out-of-date, but still offers a useful key to unlocking this mystery religion.

Theatre and Its Double, Appendix XXIV, 140. IV.242 in French edition.

Goodall 1994, 18.

Letter to Jean Paulhan, cited in Morris, 49.

Theatre and its Double (Letter to Mr R. de R.), 74.

Summary of Jonas, 42.

http://www.gnosis.org/naghamm/apocjn.html

Jonas, 164ff.

Jonas, 44.

Jonas 45, 82, passim.

Apocryphon of John 55:18-56:17, in: Jonas, 92.

Ophitic Summary of Irenaeus (I. 30. 7), in: Jonas. 93.

Jonas, 93.

Valentinian Gospel of Truth 18:16-24, in: Jonas, 78. Cf. Jonas, 67.

Second Letter to J. P., 73.

CWI, 166-167.

CWVII.25 (French edition), in: Goodall, 21. The English translations of his Collected Works Volumes 5 and 6 seem out of print—I cannot find them anywhere.

Ibid.

Sontag 1980, 18.

Artaud, Collected Works (French edition) XIV.54, XIV.107, quoted in Morfee, A. Antonin Artaud’s Writing Bodies (2005), 174. My translation here. I think grayasse (-asse is a pejorative adjectival-ending, hence ‘gross’) just means grey. Many of his early poems are also couched in disgusting language. See also Jannarone, K. Artaud and His Doubles (2010), 197-8. Artaud’s Theatre and the Plague essay is a particular highlight too:

On Suicide—CWI, 157.

Goodall, 49-50; Carrouges, M.: Andre Breton et les donnees fondamentales du Surrealisme (1950), 22-23.

Carrouges 1950, 22.

Artaud (French Collected Works), IX.156, quoted in Goodall, 53.

Goodall, 53.

Goodall, 53.

Goodall, 51.

Artaud (French Collected Works) I.214, quoted in Goodall, 51.

TD, 73.

Artaud Art and Death, quoted in Sontag 1980, 56.

Cutsinger, J. S. Paths to the Heart: Sufism and the Christian East (2004), 3, n. 6 (Ware); Cutsinger, 19 (Ware); Cutsinger, 86 (Rossi).

Quran 33:41 (al-Ahzab): O believers! Always remember Allah often (Khattab tr.).

Cutsinger, 37 (Nasr).

Cutsinger, 39 (Nasr).

Cutsinger, 39 (Nasr).

Quoted in Schimmel, A. As Through a Veil (2001), 130.

Cutsinger, 3 (Ware); quoting a number of other writers: Massignon, Thomas Merton, Dorothy C. Buck.

Cutsinger, 4 (Ware).

Cutsinger, 35 (Nasr).

Cutsinger, 5 (Ware), quoting Rob Baker, “Merton, Marco Pallis, and the Traditionalist”, in Merton and Sufism, 256.

Cutsinger, 5 (Ware), quoting Frithjof Schuon, Christianity/Islam: Essays on Esoteric Ecumenicism (1985), 89. Ware notes that Schuon also quotes the Hindu Lalla Yogishwari “My guru gave me but a single precept. He told me: ‘From without, enter into the most inward place.’” I would also note ‘Know thyself’ at Delphi.

Louis Aragon, ‘Fragments d’une Conférence’, La Revolution Surréaliste, 4 (1925), 25, in: Goodall, 39. Translated by Goodall.

TD, 90.

TD, 43.

TD, 82.

Bataille, G. The Absence of Myth: Writings on Surrealism (1994), tr. Michael Richardson, 43.

Curtin 2010, 255.

G&K, 246.

G&K, 39.

G&K, 69.

G&K, 346. Dominick Dunne, Vanity Fair.

https://thecreativelife.net/scenius/

Both G&K, 300.

Innahum kanoo itha qeela lahumla ilaha illa Allahu yastakbiroon

Wayaqooloona a-inna latarikoo alihatinalishaAAirin majnoon?

Dr. Mustafa Khattab translation.

Goodall, 7.

H&L, 43:45.

G&K, 284.

G&K, 284.

Dior Haute Couture Freud/Fetish (A/W 2000-1); Dior Ready-to-Wear: Trailer-Park Chic (S/S 2001); Dior Haute Couture Comic Strip Warriors (S/S 2001); Dior Haute Couture Creating a New Dance (A/W 2003-04); John Galliano Blanche DuBois (S/S 1988) and Dior Ready-to-Wear Tough Chic (S/S 2003); Dior Haute Couture Empress Sissi/Zsa Zsa Gabor (A/W 2004-05); Dior Haute Couture Madame Butterfly (S/S 2007); see Taylor, K. Galliano: Spectacular Fashion (2020) for more.

G&K, 232-3 .

H&L, 1:15:25. Anne Nelson (his agent).

H&L, 45:10.

G&K, 125.

Shafer, 155.

TD, 73.

Dryden, Vergil, Aeneid IX.431-432.

Barber 1994, 7

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/foucault/#HistMadnMedi

Foucault, 278.

TD, 88.

H&L, 1:16~

Finter, H. and Griffin, M. “Antonin Artaud and the Impossible Theatre: The Legacy of the Theatre of Cruelty”, TDR Vol. 41, No. 4 (1997), 17.

Ibid.

Bataille, 44

http://vieux.colombier.free.fr/historique/historique6.shtml